For many people, Disco is synonymous with Saturday Night Fever, collared shirts, platform shoes and sequins. Inseparable from the party, a living memory of the 1970s, mocked and even vilified in the mid-1980s, this musical genre, long considered minor, has become a manifesto of emancipation for minorities and a wonderful outlet in troubled times.

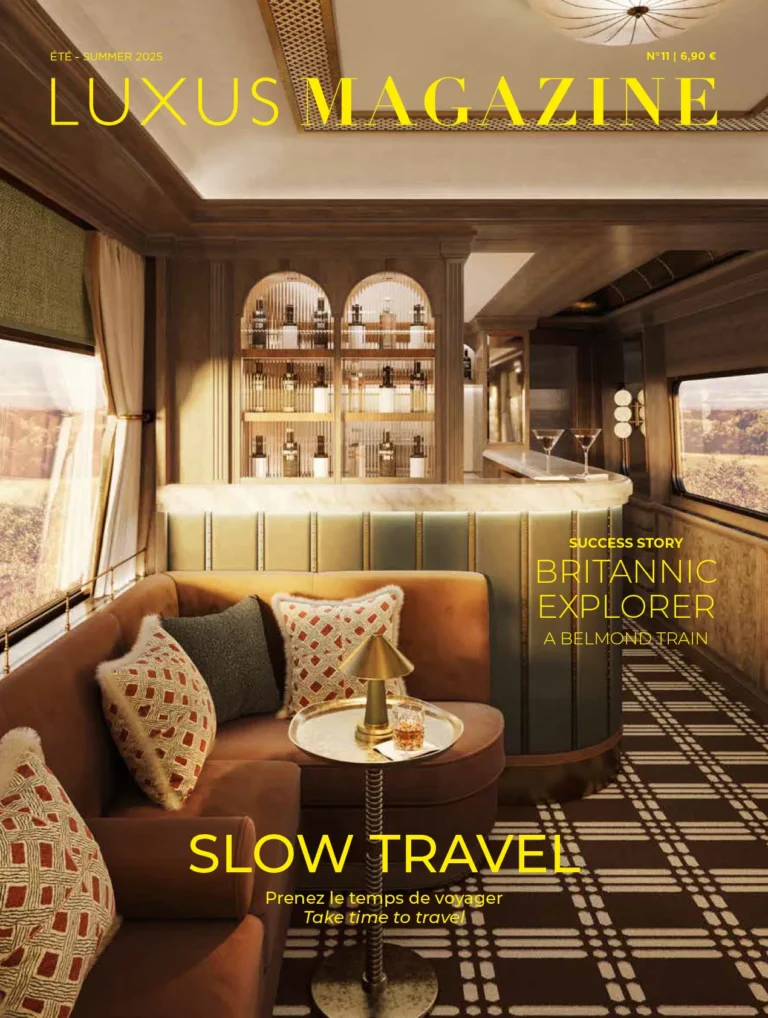

Born in the New York underground and today the soundtrack of all the most chic places on the planet, Disco has not had its last word and the Philharmonie de Paris is paying tribute to it with Disco I’m Coming Out, an exhibition running until August 17.

This more hedonistic variation of black music appeared in 1972, in an America that was losing its bearings. Officially abolished, segregation (based on race, color and sexual orientation) was then still in force in a country traumatized by the Vietnam War and a US President, Richard Nixon, who resigned against a backdrop of the Watergate scandal. Disco thus appeared like a beacon in the night.

This music could have been nothing more than a will-o’-the-wisp, relegated to a simple relic of the past, but the opposite occurred.

Long before the Eurodance of the 1990s, cherished by Gen Z and following the fall of the USSR and the Berlin Wall, here is the international history of a genre that has since regained its acclaim, serving as the basis for the emergence of electro groups that are ambassadors of the French Touch such as Daft Punk and Justice.

Born in the heart of New York… in the 1970s

Like punk before it and hip-hop after, Disco took its first steps in a period of crisis.

It was born in the early 1970s in a dilapidated New York, plagued by crime, urban violence, the ghettoization of African Americans and drug trafficking.

The movie Taxi Driver (1976) by Martin Scorsese accurately reproduces the misery and squalor of the Big Apple at the time, with its rundown buildings and unsanitary sidewalks, populated by an underworld crowd drawn to prostitutes and narcotics.

In his seminal essay on the cultural analysis of the disco movement, Turn The Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco (2008), Peter Shapiro pulls no punches in describing the situation at the time in his introduction: “Disco may have shone like a diamond, but it stank of shit. Whatever the elegant and sophisticated veneer under which it was concealed, it was nonetheless born, like a worm, from the rotten core of the Big Apple.

Faced with rising insecurity, whites fled to the suburbs while the poorest crowded into downtown New York.

In 1975, the city, on the verge of bankruptcy, decided to attract investors and the world of finance by offering tax breaks. One of the most famous developers, Donald Trump, obtained 40 years of tax breaks to build luxury hotels and apartments.

Nationwide, segregation may have been officially abandoned, but it continues to affect African Americans. Latinos and Italian immigrants are also discriminated against.

As for gay men, they are still prosecuted by the police, who are used to violent raids during which members of the LGBTQI+ community, including drag queens, are beaten up by the police. In the early 1970s, homosexuality was illegal in 49 American states. Dancing with a person of the same sex was just as illegal. On the night of June 28, 1968, one of these police raids on one of the city’s few gay clubs, The Stonewall Inn, turned into a riot. This episode marked the beginning of the struggle for the rights of the homosexual community. That evening, two slogans were chanted by the crowd: “Gay Power” and “We Shall Overcome”. The latter is directly taken from the civil rights movement in favor of African Americans.

It is in this context that marginalized communities will lay the foundations for an openly sexual and hedonistic sound.

Gathering in clandestine venues, mainly in Brooklyn, Harlem and the Bronx, they can freely indulge in lascivious dancing and set their own rules.

A sonic crossbreeding

The history of disco sound is an anomaly in musical history.

Usually, a musical genre came from a group of musicians from the same geographical area. However, disco comes from different musical sources, which were themselves selected, promoted and modified by emerging artists: the deejays “diggers” (in search of rarities and forgotten musical gems).

Initially, these deejays or “record store owners” presented themselves as a less expensive alternative to live bands, content to play recorded music in a few cramped dance halls, or even converted swimming pools and saunas. They soon gave a name to these nightclubs with garish lights and distinctive percussion: discotheques.

It was in one of these, the Loft (Soho), that a certain DJ David Mancuso had the idea of extending the memory of hippie bacchanalia and brotherly love to a mainly black, Latino and Italian audience.

In the early 1970s, these DJs played hits from the previous decade: psychedelic rock pieces inherited from the hippie years, jazz and, above all, forgotten funk, soul and rhythm & blues tracks. Some began to break free from the role of simple “record pusher” and to speed up the tempo. The first remixers thus bring out the drums and bass more.

Isaac Hayes with his Theme From Shaft (1971) and its iconic wah wah guitar is one of the first proto disco sounds.

David Mancuso is one of the first to play the longest track on the album People… Hold On by Eddie Kendrick, former lead singer of the Temptations, in a club. It is officially the first disco track in history. At 7 minutes and 30 seconds long, the feminist anthem “Girl You Need a Change of Mind” (1972) has the advantage of keeping the audience on the dance floor for longer, as well as alternating tempo variations, starting at 96 BPM before finishing at 110 BPM.

In the same year, David Mancuso – him again – unearthed the 45 rpm Soul Makossa by Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango in a Caribbean record shop in Brooklyn. A radio programmer came across the track at one of the DJ’s parties, propelling it into the American charts.

Music created in the studio, disco presents itself at the crossroads of musical genres but strongly tinged with Afro and Latino cultures with jazz fusion, blues and salsa motifs for the melody and gospel for the vocals.

Disco benefits from an electronic orchestration including strings and brass before synthesizers made their appearance the following decade. Conceived as a music for dancing, the genre favors rhythm and orchestration over lyrics and melody.

Disco eventually completed its transformation by adapting Philly Soul, or the sound of Philadelphia, another metropolis located in the Rust Belt, hit by deindustrialization and rising unemployment, for the white market. Radio stations and nightclubs in New York and Miami would then serve as a sounding board for the movement.

This Philly Soul is characterized by pathetic and flamboyant pleas and above all a lush orchestration.

It was the group Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes with their song The Love I Lost (1973), singing about lost loves in the style of a modern-day Eugene Onegin, that laid the foundations for disco rhythms. The group’s drummer, Earl Young, who had already worked on Jerry Butler’s One Night Affair and The O’Jays’ Love Train, had the idea of supporting each beat with the bass drum and not with the snare drum as the Motown label did. When asked, he added, “I added the hi-hat on the backbeats and a funky pattern on the snare drum.” To the BBC, he explains, “It’s a walking sensation. So when people hear that, they automatically want to move something.”

With this beat, he created the tempo “Four To The Floor”, or four-four time.

Marc Cerrone explains that it was not easy to promote musicians at a time when the emphasis was mainly on singers. The emphasis on percussion was for a long time met with incomprehension from French record companies, earning him the nickname ‘the lumberjack’ for a time. A founding father of the French Touch, Cerrone explains that “disco is music made to set the mood for the body, not to listen to the lyrics but to dance to them.”

Disco becomes mainstream

In 1973, Barry White and his Love Unlimited Orchestra released Love’s Theme. A languid piece celebrating the unlimited love between a man and a woman that was destined for the bin at the 20th Century label. Saved at the last minute by DJ Nicky Siano, who was working at The Gallery, the record was such a dancefloor hit that the label was forced to release it as a single. From then on, producers realized that by daring to release long format tracks, they could be played more easily in clubs… and break into the charts.

But soon, an event would catapult disco beyond its original community to white populations.

The OPEC member countries, meeting in Kuwait, declared an embargo on oil shipments to countries supporting Israel: this was the first oil crisis. Between October 1973 and January 1974, the price of a barrel of crude oil quadrupled, rising from $2.3 to $11.6 (the equivalent of $50 in constant 2008 dollars). From then on, a large proportion of American youth faced mass unemployment and uncertainty.

Disco and discotheques, less expensive than tickets for rock concerts, become the ideal escape for disenchanted youth. Nightclubs began to spring up everywhere in the United States and Europe. Far from the stereotypical locker room of Saturday Night Fever, people dressed up and got all dolled up to go dancing on Saturday night, at a time when economic and social constraints were accentuating individualism.

With its original emancipatory message and beyond the lyrics that mainly encouraged people to let loose and dance the night away, disco succeeded in conveying a number of feminist messages through the figure of the diva. Donna Summer was thus stripped naked in 1974 with her more than suggestive Love To Love You Baby, a 16 minute 50 second ode to anti-macho love.

Two years later, a more industrial disco sound began to saturate the airwaves with hits designed for private parties. The satirical track Disco Duck by Rick Dees and his casts of idiots poked fun at the musical genre and broke into the American charts. This seemed to signal the end of the movement, but the opening of a nightclub changed the course of history forever.

On April 26, 1976, at 10 p.m., the Devil’s Gun by CJ & Co blared out over the brand-new dance floor at 273 West 54th Street. Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell had succeeded in transforming the former CBS television studio into a temple of partying: Studio 54 was born. With a strict door policy for the beautiful people, great music, flamboyant drag queens, tasteful interior design and dynamic state-of-the-art lighting, the establishment stood out and became a hotspot for celebrities and the golden youth. Andy Warhol, Michael Jackson, Debbie Harris, Margaret Trudeau and Salvador Dali were regulars. Designer Halston, a regular at the club’s parties, drew inspiration from the vibes and glitz of the place to create a festive fashion. He organized a legendary birthday party for Bianca Jagger, immortalized perched on a white horse, arriving to the Rolling Stones’ Sympathy for the Devil. The decadent spirit of Studio 54 made the front pages of newspapers.

The queue inspired the artists of the time, Cerrone had the idea of including pre-party discussions as an introduction to his Love in C Minor (1976). This opus, which has not yet found its audience in France and has the feel of a “last album”, ends up in the United States through a delivery error. A record store waiting to replace faulty Barry White records receives the album with Cerrone‘s provocative cover. In clubs, the record is a hit. A pirated version hits the shelves. Without further ado, the Frenchman goes to New York to defend his copyrights and obtains the support of Atlantic Records.

Rejected by the Studio 54, a certain Nile Rodgers, bass player for the group Chic, had the idea of mocking these beautiful people with their improbable looks with his song that became a real hit: The Freak (1978).

In 1977, the disco movement was immortalized and went international with the musical film Saturday Night Fever and John Travolta’s frenzied dance. With his character Tony Manero, an Italian immigrant, a warehouse worker by day and an unconditional night owl at Club 2001 Odyssey by night, he portrayed these average Americans in search of self-fulfillment. An Australian-British pop group with high-pitched vocal harmonies looking for a boost, the Bee Gees became the first white group to sing disco. Between Staying Alive, More Than a Woman and Nightfever, the film’s soundtrack is full of the group’s hits. Extremely popular, it sold 25 million copies between 1977 and 1980, becoming the biggest hit in musical history before being dethroned by Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1982.

At that time, Giorgio Moroder returned to the charts with I Feel Love by Donna Summer, Gloria Gaynor sang her anthem of resilience I Will Survive, while YMCA by the Village People, not yet co-opted by Donald Trump, celebrated queer culture. The latter group was the work of two Frenchmen, Henri Belolo and Jacques Morali.

As disco gained international popularity, the excellence of Abba, Boney M, Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones and Imagination, among others, rubbed shoulders with the mediocre. More and more major artists, whether in decline or out of pure opportunism, seized upon the movement.

In France, Claude François was struck in mid-flight just as he had taken the disco turn with his final album Magnolia Forever (1977), which included his eponymous hit and Alexandrie Alexandra. Dalida sang Laissez-moi danser (1979), while Yeye artist Sheila enjoyed a second career with the band B Devotion and their hit Spacer (1980).

On the Anglo-Saxon side, Blondie, Rod Stewart, and especially the Rolling Stones with Miss You (1978) thought they had struck gold. But the overload of disco and highly formatted, commercial hits angered rock fans. On the scent of racism and homophobia, a crowd of young white people gathered on July 12, 1979, at Comiskey Park for Disco Demolition Night. It was the first auto-da-fé of disco records, organized at half-time of a baseball game. In the same year, Studio 54 closed its doors for the first time due to the tax evasion charges against its owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager. The nightclub never recovered from this, closing for good in 1986.

For Nicky Siano , DJ at The Gallery club, the anti-disco movement, which chants “Disco Sucks”, is a result of the decline in quality. “In the beginning, you would buy a disco-bannered record and it would be a great song, no matter which one you picked out but then, some executives in diapers decided ’let’s put disco on these records we wanna sell’ and it wasn’t good music anymore. It was garbage.”

But behind this denigration of this musical genre, one can already perceive the challenge to a new masculinity advocated by Disco imagery with men’s fashion that is closer to the body, more colorful and more revealing.

Disco’s Alive

Like Victor Frankenstein’s creature, the undead returning from the dead, disco is still very much alive.

When Steve Rubell, the legendary owner and face of Studio 54, died of AIDS in 1989, his sidekick Ian Schrager returned to business and switched to hospitality, creating the boutique hotel concept with The Edition Hotels in 2015.

In pop culture, disco makes a few notable appearances. In 1998, Whit Stillman’s film The Last Days of Disco featured a couple of disillusioned young graduates (including Chloé Sevigny and Kate Beckinsale) escaping from a complicated professional life by going out dancing in the early 1980s. More recently, the films American Hustle (2013) and The Nice Guys (2016) feature numerous scenes celebrating disco culture. As for series, The Get Down (2016) produced by Netflix goes back to the roots of the early days of hip-hop and deejaying, with a gospel singer heroine dreaming of becoming a new disco diva, Vicki Sue Robinson style with her Turn The Beat Around.

In the music world, the French Touch movement, at the dawn of the 2000s, saw a new generation of DJs reclaim the great classics and forgotten gems of disco such as Cassius, Modjo, Benjamin Diamond, Superfunk, Dimitri From Paris and Bob Sinclar. Among them, groups like Daft Punk with their album Discovery (2001) have restored disco to its former glory with tracks like One More Time and Veridis Quo. This movement was also featured at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games, with Cerrone performing his hit Supernature at the closing ceremony.

Across the Channel, disco is also enjoying a reprieve at the same time with Sophie Ellis Bextor performing Murder on the dancefloor – which will find a new lease of life with Gen Z in 2023 with the film Saltburn produced by Amazon Prime – and Jamiroquai offering a groovy sound with hints of disco.

But the disco revival came in 2013 when Daft Punk invited the bassist of the group Chic and the musical polymath Pharrell Williams to record Get Lucky for the album Access Random Memories.

During COVID, several artists held filmed live sessions, while Dimitri From Paris mixed in the deserted Parisian nightclub Sacré, Roisin Murphy unveiled new disco gems, and Sophie Ellis Bextor released a reinterpretation of the group Alcazar’s Crying At The Discotheque, which itself sampled the track Spacer by Sheila and B Devotion. In the video, she sings in several empty London venues, from Club Heaven to the O2 Arena, via the Apollo Theatre and Bush Hall.

For Cerrone, interviewed as part of the Disco I’m Coming Out exhibition, “Disco never disappeared. It had its more and less progressive moments, but it has always been played in nightclubs with electro, house, garage and EDM tracks”.

In recent years, American pop stars with an international aura such as Dua Lipa, Doja Cat and Lizzo, or European stars such as Roisin Murphy, Juliette Armanet, The Blessed Madonna, Dj Koze, L’Impératrice and Purple Disco Machine, have summoned up the nostalgic and flamboyant memory of disco, proving that the slogan “Disco is not dead” still has a raison d’être.

Read also > Flore Benguigui, the vocal imprint of the group L’Impératrice, on the move

Featured photo: © Dustin Tramel/Unsplash