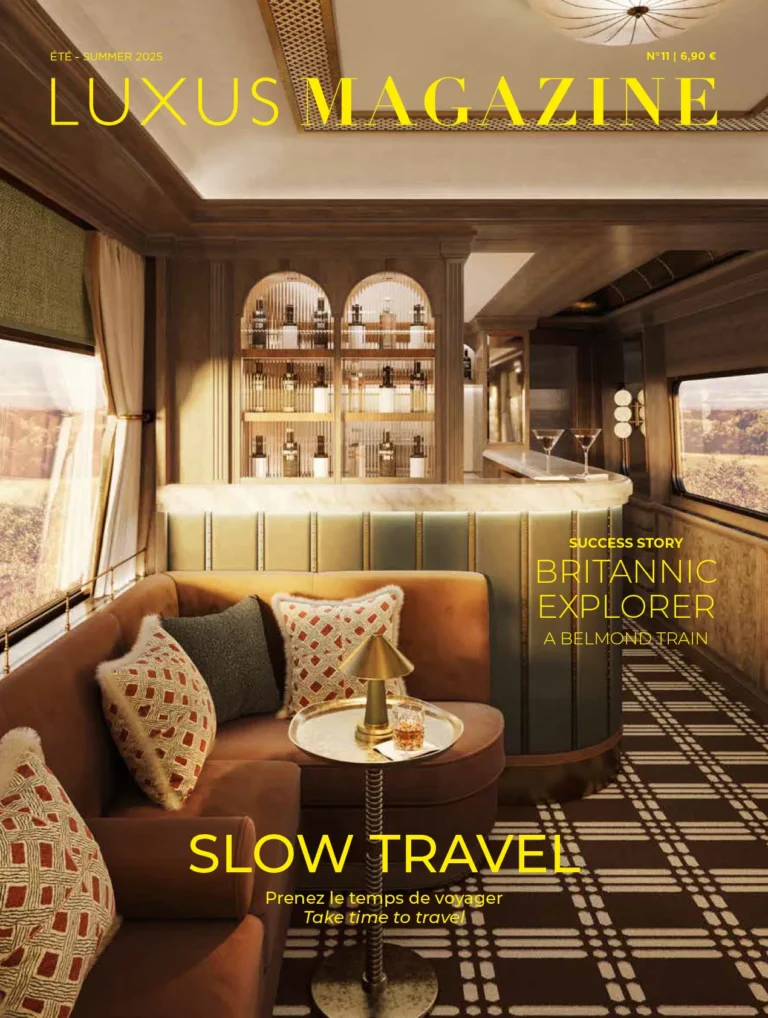

With its auspicious red and gold hues, costumed parades, family meals, firecrackers and fireworks, Chinese New Year has for millennia been one of the most festive traditional times of the year in China and in all regions of the diaspora. Following the lunisolar calendar, its dates vary, unlike the Gregorian calendar, which begins on December 31. This year, the festivities began on January 29 and will continue until February 12.

It’s not for nothing that the Middle Kingdom invented gunpowder and its recreational version, fireworks, back in the 7th century (Tang dynasty).

The Chinese New Year once again promises a temporary urban exodus on a massive scale, with almost 3 billion journeys enabling Chinese people to return to their hometowns and visit their families, to the extent that many commentators are calling the period “ the world’s largest annual human migration ”, in a country with 1.4 billion inhabitants (18.4% of the world’s population). And this year, the country that remains the world’s largest producer and consumer of automobiles, expects an inflation in the number of car trips over the period (7.2 billion).

A privileged moment for millions of people, especially workers, to be reunited with their families, these celebrations are particularly important in China and throughout South-East Asia, from Thailand to Singapore, via Korea and Malaysia.

This Chinese New Year, or “Tet Festival” in Vietnam, under the sign of the wooden snake, marks the beginning of the Chinese luni-solar calendar. It coincides with the start of the second new moon following the winter solstice.

Also known as the “Spring Festival ” (Chūnjié), these festivities, which have their origins in agriculture, this year include 8 official public holidays (from Tuesday January 28 to Tuesday February 04, 2025). However, the celebrations can be extended to the fifteenth day of the first lunar month, marking the Lantern Festival, i.e. February 12, 2025.

In addition to New Year’s Eve, the Chinese government has decided to grant two extra days of annual vacation this month, bringing the total to 13, with New Year’s vacations starting a day earlier this year than ever before!

As for the history of Chinese New Year, it’s rooted in the tradition of agricultural festivals, with many myths and legends about the struggle between good and evil.

A legendary but fearful monster

The beginning of the Chinese New Year is Nian.

While the word now means “year”, it has long been the name ofa legendary monster.

With the head of a lion and the body of a bull – some legends even mention a fabulous horned animal – the beast used to descend from its mountain once a winter to devour the children and cattle around it.

Appearing only at nightfall and departing at first light, the villagers began to understand the beast’s habits and better prepare for its arrival. To give themselves courage for the famous night of vigil, they didn’t hesitate to organize big dinner parties by lantern light, barricaded in their homes.

It didn’t take long for them to discover the monster’s weakness: a terrible fear of fire, noise and red.

On his return, the villagers banged on their copper pots, switched on their lights, painted their doors scarlet and hung garlands of scarlet paper in the streets. The monster scurried away.

One day, the star god Ziwei came down from his mountain to chain Nian. But the locals kept this tradition alive, including the famous shousuì or New Year’s Eve meal, during which the idea is to stay up as late as possible in order to live longer – in other words, to “stand guard for the year”.

It’s easy to understand why all the stratagems used to guard against the monster’s attacks have been preserved to serve an apotropaic function (warding off the evil eye).

And so, since that day, the arrival of Nian has been synonymous with the detonation of firecrackers and fireworks, the color red in the house as well as on oneself, and big feasts. The figure of the monster is present in the form of costumed parades interspersed with the dragon or lion dance. It’s also a key moment in any store opening in Asia. The aim is toward off evil spirits and bring good luck.

Money and demons

Another New Year tradition is the exchange of red envelopes, or hóngbāo. Although these usually containmoney, the container is at least as important. Bright red heralds good luck and prosperity.

Legend has it that, like the Nian, the demon Sui used to visit children on New Year’s Eve and pat them on the head, causing them to run a high fever. Parents, eager to protect their children, did everything possible to keep them awake. One evening, a child was given eight coins to play with all night long. But to no avail, he fell asleep with the coins next to him on his pillow. However, when the demon appeared at the foot of his bed to touch him, the light from the coins dazzled him and frightened him so much that it never appeared again.

Another legend mentions the presence of the Eight Immortals in the envelope, each corresponding to a coin. Originally mere mortals, they appeared in the form of people or talismans, and became symbols of the struggle between good and evil. Thus, for example, Zhong-li Quan was associated with a magic fan capable of reviving the dead, while Li Tie-guai is represented with a cane and a calabash containing alcohol, representing health and above all the ability to overcome life’s ups and downs.

This is another example of the importance of the lucky number 8. In this game, however, any ticket containing the number 4 is to be avoided, as the pronunciation of the number sounds like the word “death”.

These special envelopes, held with both hands, areexchanged between friends, family (including extended family) and colleagues. As it is customary for each new lunar year to be marked by renewal, new banknotes or those freshly withdrawn from cash dispensers prevail. However, with the development of digital technology, hóngbāo can be dematerialized. Wechat has thus become one of the preferred channels for distributing red envelopes.

Carp and Prosperity

Apart from the lion dance, another animal completes the bestiary of good luck in China, to the point of appearing as a decorative element at the table as well as in the streets: the carp.

This fish is called Li Yu in Chinese. Yu is pronounced like the words “profusion” or “abundance”, so it’s not uncommon to see carp motifs on red envelopes intended for students to bring them luck and prosperity.

Similarly, the image of a child holding a carp is widespread in China, and can also be used as a decorative element.

Carp-shaped vases also symbolize exam success. Legend has it that, at spawning time, if the sturgeon of the Yellow River – often confused with the carp – managed to swim upstream, it became a dragon.

In the same vein, the motif of a pair of goldfish, or “golden carp”, appeared during the Shang and Zhou dynasties. Associated with gold and jade, it represented “abundant wealth”.

Even more surprisingly, the rooster motif on its rock also heralded business advantages. The word chicken (ji) is pronounced like the Chinese character for “prosperity”, while “rock” and “coin” share the same pronunciation (shi).

Sharing and ravioli

An auspicious number par excellence, 8 is also found on the plate, so it’s customary, especially during Chinese New Year festivities, to serve 8 dishes. Among them, a whole fish – the word fish being close to that of abundance – or duck.

For example, duck stuffed with “eight treasures ” is traditional in Shanghai and Guangzhou. It contains eight stir-fried ingredients, including sticky rice, mushrooms, lotus seeds, smoked ham, shrimp and lean pork. As a condiment, uncut noodles and long beans represent longevity, while mandarin oranges and grapefruit bring opulence and good luck. As forpineapple and dragon fruit, they are supposed to bring gambling luck.

But in northern China, ravioli or jiao zi ( 饺子) is king. The word is related to jiāo zi (交子) meaning “exchange” and zi (子) meaning the passage from 11 pm to 1 am. The idea is toexchange the old year for the new one over a dish of filled noodles. The superstition surrounding ravioli stems from the fact that their shape is reminiscent of yuanbao (元宝), or ancient ingots.

Lanterns and divine lull

As for the Lantern Festival, which closes the fortnight-long Chinese New Year festivities and marks the first full moon, a15th-century legend tells of divine wrath. When the Jade Emperor’s crane descended to earth, it was accidentally killed by the inhabitants of the capital city. Mad with rage, he threatened to set fire to the city on the 15th day of the first lunar month. Having learned of the God’s intention, his daughter ran to warn the inhabitants.

To calm the god’s ardor, the townspeople came up with the idea oflighting lanterns. Believing the city to be already engulfed in flames, he withdrew.

Another legend, that of an imperial order, dates back 2,000 years to the Han dynasty. An advocate of Buddhism, the Ming emperor of Han noticed that Buddhist monks lit lanterns on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month. He therefore required all homes, temples and the imperial palace to light lanterns on that evening.

Finally, the Lantern Festival has long been associated with love. In the past, however, women confined to the home were allowed to go out on this day. So much so, in fact, that some call it the true Chinese Valentine’s Day, with greater legitimacy than today’s Qixi Festival.

Although the unofficial festival of lovers is no longer held at this time, one tradition has endured. In addition to lighting lanterns and red lanterns, it is customary to eat balls of glutinous rice flour, known as Tangyuan. Its shape evokes notions of fullness, family togetherness and satisfaction of needs.

Finally, unlike the other days of the Chinese New Year, when the traditional paper lantern (Huadeng) is still popular, despite competition from more innovative materials, those at the Festival are more like giant light sculptures, in various shapes, such as those of animals.

Read also > The history of the aperitif

Featured photo: © Unsplash