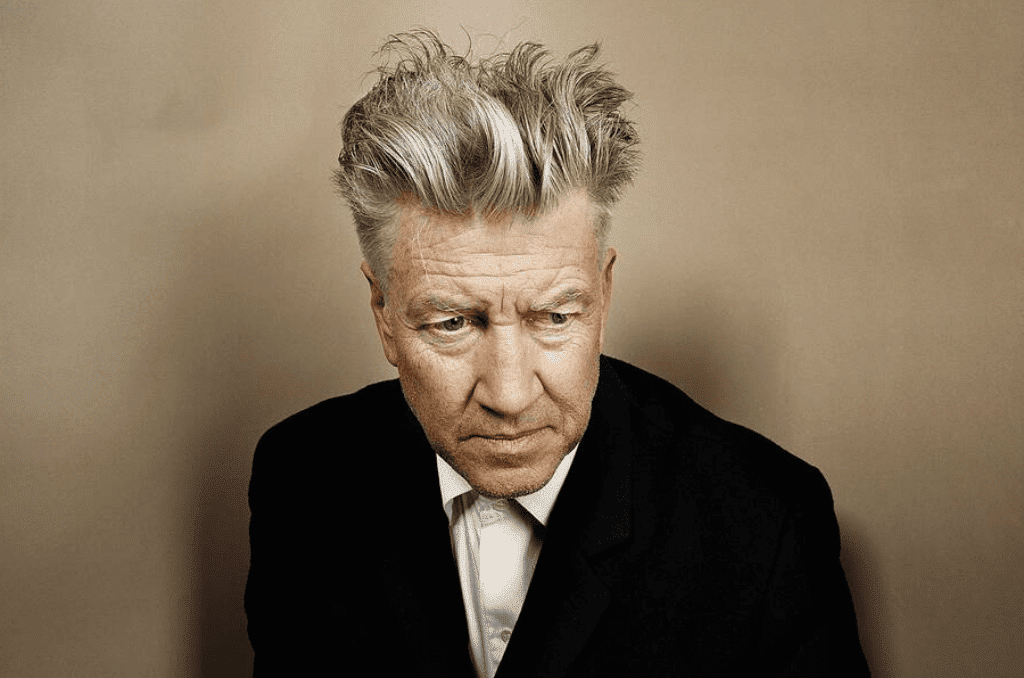

David Lynch, 78, died in Los Angeles on January 15. While the world will remember him for his surrealist films, tinged with the stuff of dreams, he also left behind advertisements for the big names in luxury goods and, even more personally, the paintings and drawings he produced in his spare time.

A graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, David Lynch came to filmmaking through drawing and painting, his graduation project consisting of creating a mini animated film around his pictorial works, in a way that was as innovative as it was amusing.

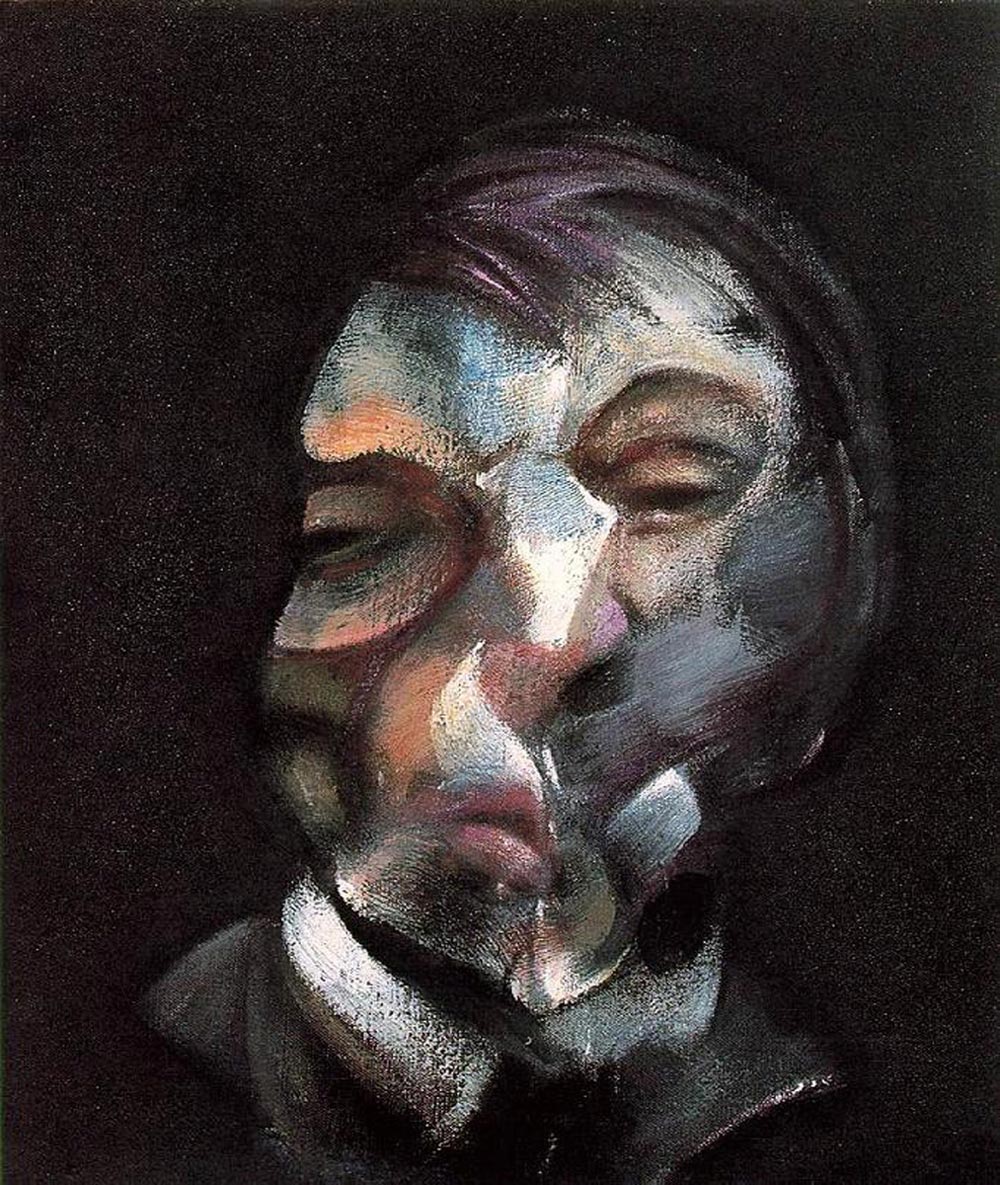

But already, his dark universe, as singular as it is disturbing but tinged with absurdist humor, is beginning to win over his fellow students and teachers. According to an equally Lynchian legend, it all started withan electric shock: his encounter with the tortured works of Francis Bacon.

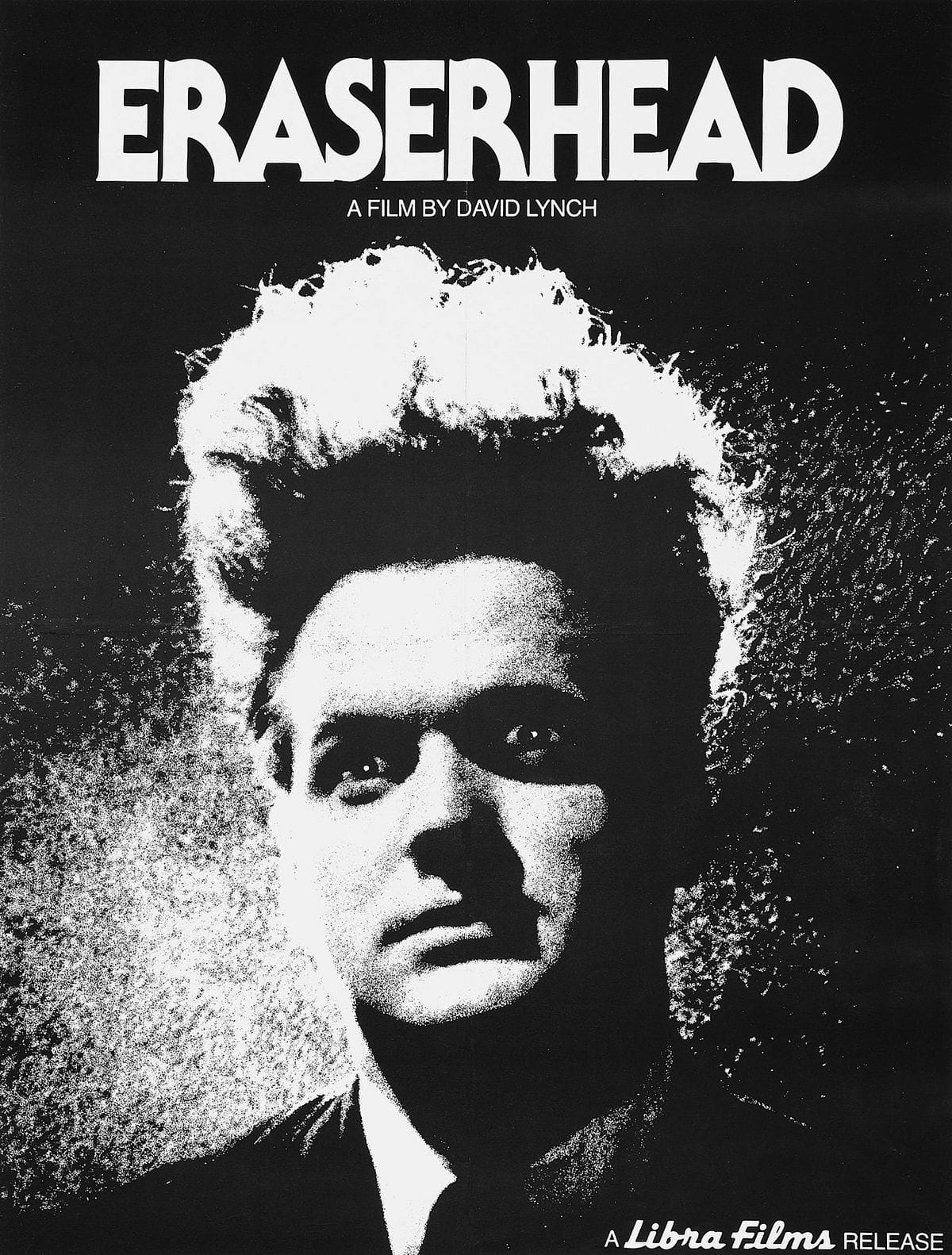

This sense of visual drama was to follow him through a dozen films over the next thirty years, some of which left a lasting impression on the retina, such as Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive and Blue Velvet. He was less fortunate on television, however, having created a television UFO in two seasons: Twin Peaks.

Freaks and false pretenses

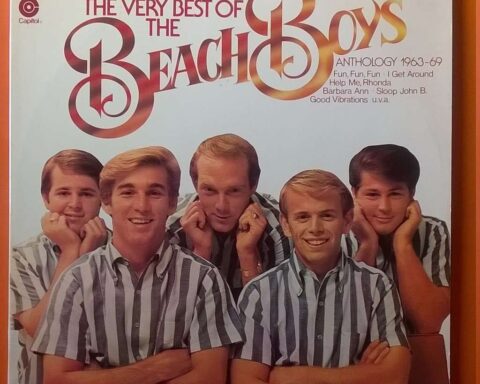

If David Lynch were a piece of music, it would inevitably be a song from the 1950s, the golden age of American consumerism. The Montana native retains a close link with his childhood memories of cherry pie, Drive-ins and Diners, retro fast-food joints with red neon lights serving burgers, fries and milkshakes. His work abounds in homage to this period, from the decor to the soundtrack. We might therefore tend to associate him with the light-hearted, innocent productions of the period. But that’s to misunderstand his taste for the bizarre, to the extent that Percy Faith’s Theme from a summer place, as naive as it is eerie in its instrumental ritornello, (too) easily sums up his character. It’s a song that’s both the candy of an era and the sanitized music of an elevator.

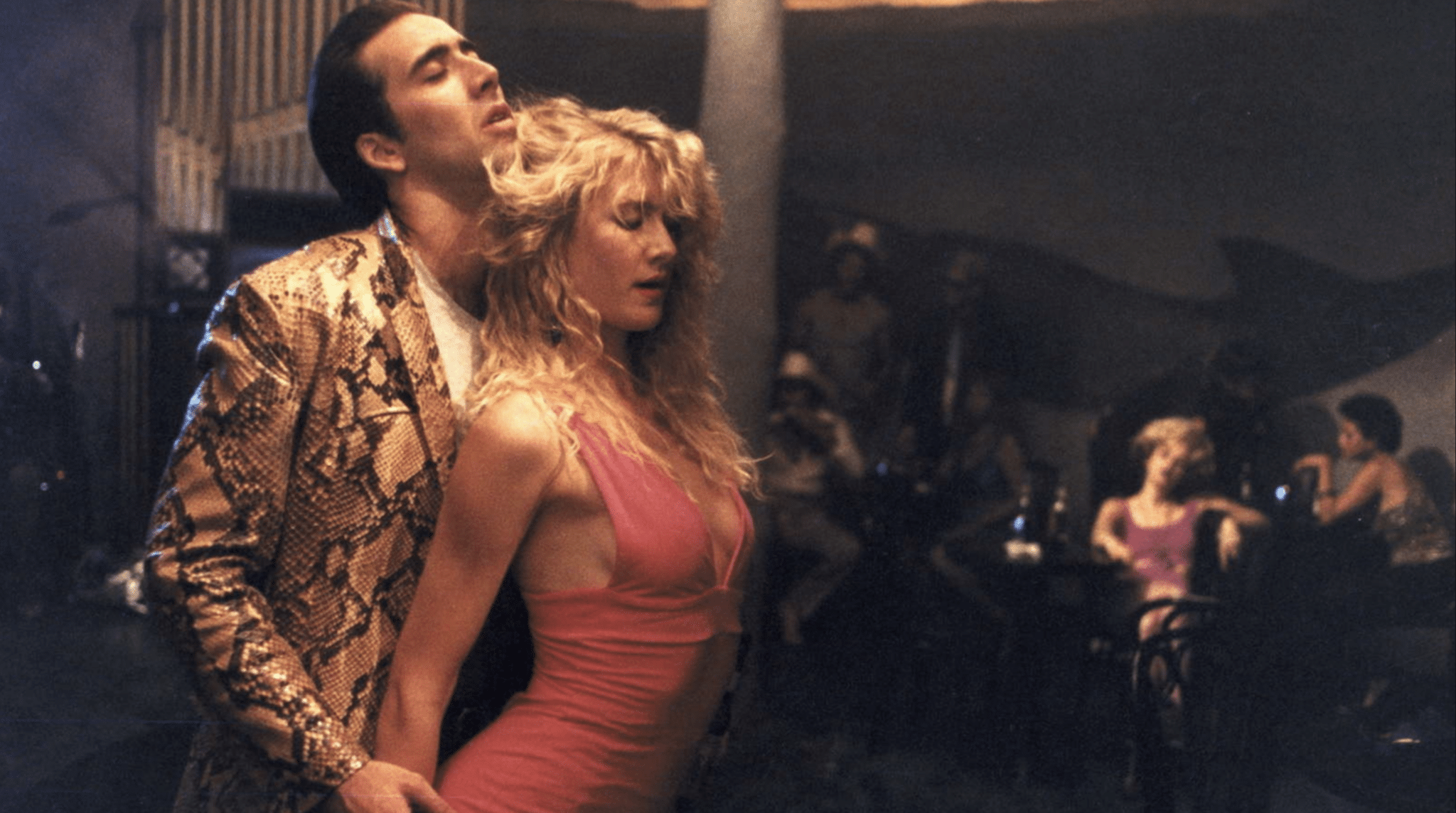

His stories are full of characters who are, to say the least, strange and even disturbing, such as “the woman with the log” and the dancing dwarf in the Twin Peaks series, the drug dealer Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) in Blue Velvet or Bobby Peru and his mistress Perdita Durango in Wild At Heart.

As one of his favorite actors, Kyle MacLachlan (Dune, Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks), recalls, he retains very precise multisensory memories of this era, such as the time he liked to enjoy his milkshakes at Bob’s Big Boy, so that they were at a certain temperature. This same meticulousness can be found in the choice of music for his films, finding in Angelo Badalamenti his sonic double.

This taste for the strange and the “freaks ” (bizarre personalities both physically and psychologically, editor’s note) is said to have been born ofa visual shock in the presence of his brother: the sight of a naked woman in the middle of the street. Neither moved nor amused, he burst into tears, imagining that the worst must have happened, even in a small town that looked too perfect to be honest. He learned a lesson that permeates all his work, namely that even the most peaceful villages are home to disturbed people who do things they’d rather keep secret.

He knowsthese small, uneventful towns well– at least on the surface – having experienced them time and again as his father, a USDA research scientist married to an English teacher, moved around. In the space of a few years, he and his family moved to remote towns such as Sandpoint, Boise (Idaho), Spokane (Washington), Durham (North Carolina) and Alexandria (Virginia). Little David could have felt uprooted and lost, but on the contrary, he manages to make friends easily.

Meeting the father of one of his classmates, a professional painter, was a revelation. David Lynch enrolled in painting studies at the Corcoran School of Arts and Design in Washington DC, before moving on to the Tufts School of Fine Arts in Boston, where he roomed with musician Peter Wolf. Here, he perfected his passion for music, but hated the content of his university courses.

Dreams and unusual liminal spaces

Another shock in his life was his move to Philadelphia, his first metropolis of residence and a place he perceived as dirty and disquieting, where he discovered a passion for industrial environments and factories.

It was in this seemingly inhospitable city that he began his reluctant pursuit of filmmaking. His studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts revealed not only a new vocation , but also a wife and mother in Peggy Reavey, a fellow student.

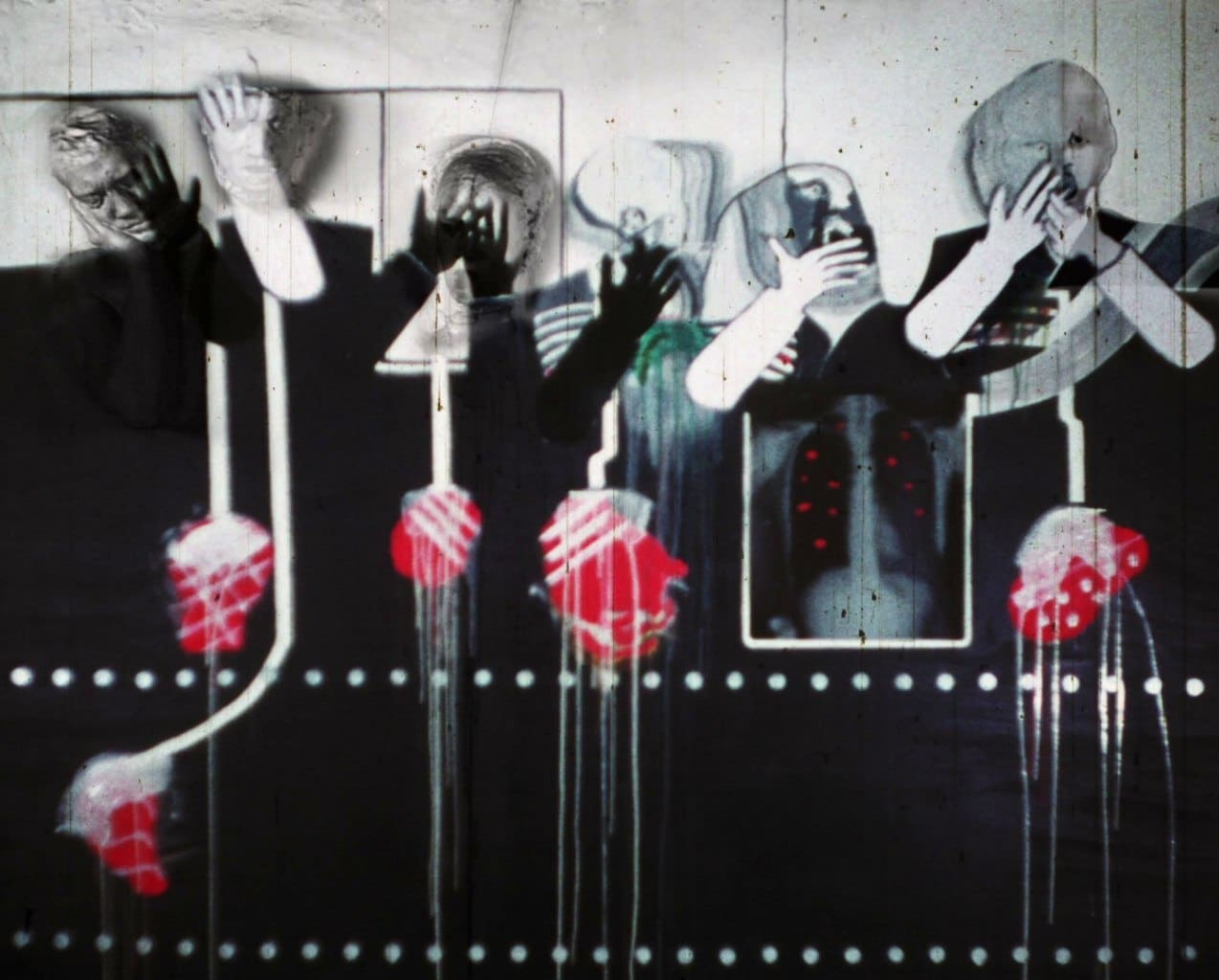

It was here, too, that he made his first short film, Six Figures getting sick (1967), based on the animation of his works of art. The result is a world as amusing as it is bizarre. His film was featured at the Academy of Fine Arts’ annual exhibition, where he tied for first prize. His second short film, The Alphabet, won him funding from the American Film Institute. The script offers a condensed version of the Lynchian spirit: a neglected child plants seeds and literally grows a grandmother to take care of him. Fantastic and absurd, his inexhaustible sources of surrealist inspiration are already at work.

From then on, he never ceased to offer dreamlike tales on the edge of dreams and their evil side: nightmares. In Blue Velvet, for example, you can hear Roy Orbison’s deliciously fifties-style “In Dreams ”. Dreams are also at the heart of Dune’s plot, as evidenced by the prologue sequence, with a real sense of narration and immersion. Using numerous subterfuges to lose the viewer, as in Mulholland Drive, he manages to abolish all reference points between dream and reality.

To mark the separation between two worlds, he usually uses conventional luminous spaces such as corridors, roads and stairwells. The director prefers to opt for theatrical red stage curtains, or even objects of no interest to the storyline, erected as portals to the other world, like the blue jewelry box seen in Mulholland Drive. After all, like the Wizard of Oz and the double-bottomed sets of his Twin Peaks series, he is “the man behind the curtain”, knowing his Lynchian mechanisms inside out. One of his inventions to create a certain unease in viewers was to have the little man in his series speak through a soundtrack recorded in reverse.

Surreal tales and film noir

For his first feature film exploring the meanders of dreams, he chose his nightmarish version with Eraserhead (1977), a horror film entirely self-produced on a modest budget ($10,000).

His singular universe draws its essence from surrealist films such as Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ or Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou. Film noir remains his other obsession: he borrows its codes, with clueless investigators, wisps of smoke and sensual women in crime-prone red make-up. His advertising for Armani picks up on this atmosphere, which is as classy as it is poisonous.

No other work inspired the filmmaker as much as Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). The character of Norma Desmond, as pathetic as she is disquieting, a fallen glory of silent cinema vainly seeking the spotlight once again, even appears visually in the equally art deco and decayed guise of an old cocotte in his film Mulholland Drive. His discovery of the aesthetics of painter Francis Bacon did the rest, or rather inspired the look of his Elephant Man, commissioned by director Mel Brooks. A veritable masterpiece on the acceptance of difference, it follows the story of a man suffering from a physical monstrosity, exhibited as a curious beast at a funfair, saved from the clutches of his managers by a kind soul, earning him the recognition of his peers.

But it was with Dino de Laurentiis’ Dune that he came up against what he called his “Waterloo”. With a budget of $40 million, the adaptation of Frank Herbert’s best-selling science-fiction novel proved too demanding, too overwhelming, not to mention that the final cut ultimately eluded him, and audiences and critics alike were not on board. Deeply affected by this commercial and personal flop – which would later become a cult work – he came out of it inoculated against Hollywood blockbusters, preferring to opt for lower-budget films and retain control over the final cut.

In 1986, he returned to the limelight with his sultry Blue Velvet, a violent thriller set behind closed doors and starring the sensual Isabella Rossellini… with whom he would have a four-year affair.

With Wild At Heart (1986), he proposed a story in his own words : “the Witch of the West – from The Wizard of Oz – stalking a couple composed of a sort of Marilyn and Elvis, two friends on the run, played by Laura Dern and Nicolas Cage, pursued by gangsters. The film takes viewers on a journey into hyper-violence, where the heroes come face-to-face with a gallery of equally bizarre characters. A composite work, the film blends multiple genres, from horror to soap-opera bubble gum romance to road movie. This rock’n’roll tale won the 1990 Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

His crowning achievement came with Mulholland Drive, a story revolving around another of his favorite themes: troubled identity and the figure of the double. The film follows a young blonde actress, Betty, played by Naomie Watts, in her quest for fame in Hollywood, who meets a confused brunette, Rita, played by Laura Harring. The City of Angels – which the director knows from his time there – is depicted in all its duality, with its spotlights and shadows.

But above all, going much further in its radical experimentation than “Lost Highway”, this whodunit, conceived as a mental labyrinth oscillating between reality and fiction, disconcerted many a filmgoer on its release in 2001. The magnetic, enigmatic adagios of Angelo Badalamenti, the director’s faithful travelling companion, complete the film’s stupefying effect. In 2016, the film was named best film of the 21st century in a BBC Culture poll of 177 critics. Not bad, for what was initially just an abandoned TV pilot, shot in 1999 and completed with the help of Studio Canal funding.

An adept at radical experimentation, David Lynch doesn’t confine himself to his standard fare, which is shrouded in fantasy. He also occasionally offers films that are unclassifiable in his filmography, such as “The Straight Story” (1999), a road movie between Iowa and Wisconsin, involving a man, Alvin, who, after a fall, decides to visit his sick brother, Lyle, whom he hasn’t seen for a decade, on his lawnmower.

Despite award-winning films in France (Cannes Film Festival, Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival…), hailed for their chiseled storytelling, singular atmosphere and polished soundtrack, the director is shunned at home. He will have to wait until 2019 for an honorary Oscar. On seeing the statuette, he madea remark as lynch-mob-like as his films: “you have a very interesting face”.

Read also > Tim Burton: Master of the Dream Fantasy

Featured Photo: DR