Economist and activist Linda Rama is much more than just the wife of Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama. Journalist Màrio de Castro met her for Luxus Magazine and brings you an exclusive interview.

Who is Linda Rama, wife of Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama? Linda is an economist and graduated from the University of Tirana in 1987. She obtained a master’s degree in economics from the Central European University (CEU) in New York in 1993. She also holds a doctorate in economics. She has been a lecturer in international finance and public finance at the University of Tirana and a lecturer in public policy and public risk management at the European University of Tirana.

From 1993 to 1999, Linda Rama was a consultant for the National Privatization Agency under the auspices of the Council of Ministers and served on the supervisory board of the Stock Registration Center, which preceded the establishment of the Albanian Stock Exchange.

Linda is co-founder of the Human Development Promotion Center (HDPC), one of Albania’s first think tanks. She is an author, co-author, and research expert in areas such as governance, human development, the labor market, education, social protection, and private sector development in Albania and neighboring regions.

Linda Rama is co-founder of the Albanian Alliance for Children and an advocate for the “Say Yes For Children” movement. She has long been committed to defending human rights and civil society, particularly those of children and women.

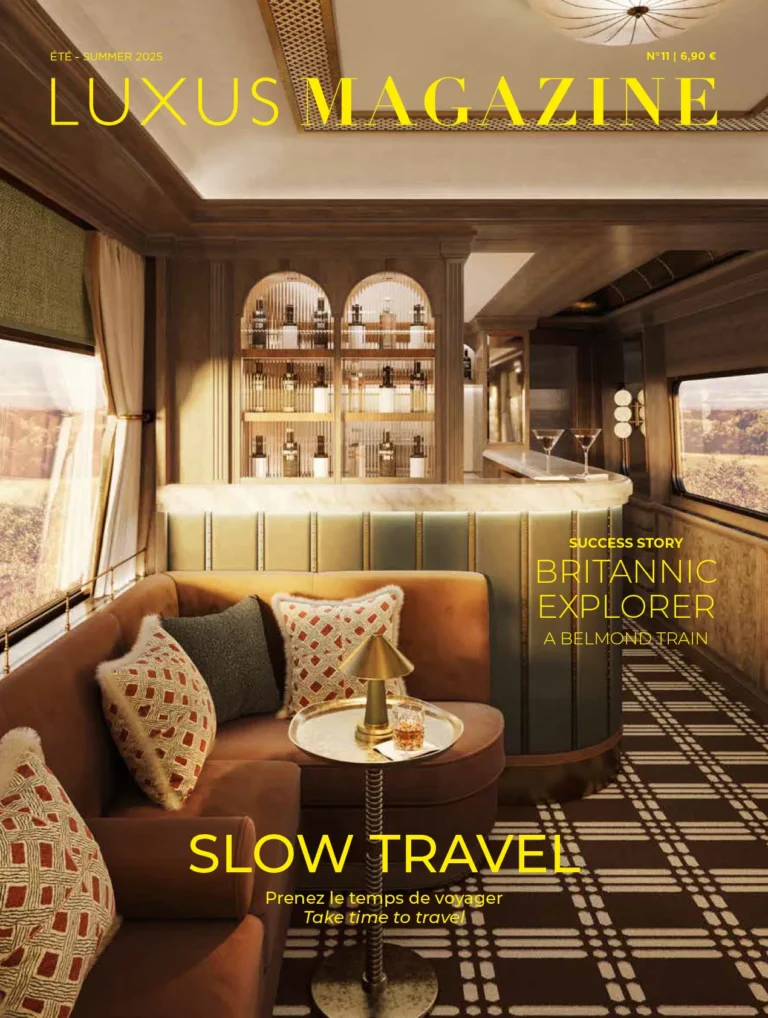

The booming and sustainable Albanian tourism sector is the official host country of ITB Berlin 2025. Tourism is a fast-growing sector. In 2024, 11.7 million visitors traveled to Albania. The majority of foreign direct investment (FDI) came from Turkey, followed by Italy. According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), there are five reasons to invest in Albania: a liberal and reformist investment climate, an optimal geographical location, economic growth and stability, the development of infrastructure for high-end tourism, and a strong focus on sustainable development and the environment. Hotels, airports, marinas, art centers, museums, government initiatives, and infrastructure improvements are among the factors contributing to record growth in tourism.

A breathtaking coastline, rich historical sites, a vibrant culture, natural beauty, and modern hospitality, along with promising projects for the future, are putting Albania on track for new economic and social records.

Interview

M de C: Would you call yourself a woman’s human rights defender?

Linda Rama: Albania is at the top of the list on the United Nations chart for women’s representation in politics and society. I find myself and my generation as civil society activists in a position to fight for women’s rights and women’s representation. We are not doing this with our own interests in mind. I think that the first mission is to make a difference, because we are supposed to make a difference as women, and there are so many things that we can do better than men. And making a difference is not to just doing it, it is to keep on doing it!

M de C: Do you think the battle for women’s rights is never-ending?

Linda Rama: To fulfil whatever functions you have or terms of reference you have in government the difference has to be made in parliament. For instance, when you know that something is not happening in a certain community, you shouldn’t ever feel that you must accept it. This status quo should be stopped. We are raising another generation now, one completely different from my generation, so you must fit with whatever this new generation needs. Although Edi has been very supportive – and I’m very grateful for people like Edi and others who are somehow conscious of the need to increase women’s representation – I don’t feel this is happening, and sometimes I become a little frustrated.

M de C: As a woman born and bred in Albania you’ve made a successful post-communist transition. What is your vision for the future of women in Albania?

Linda Rama: I grew up with a grandmother who worked full-time in the home, who invested all her talent, intelligence and authority in the family without ever having a chance to prove herself beyond those walls. My mother is the typical woman of socialist realism.

She worked at work and at home, without ever removing her attention and care on our well-being, encouraging us to get an education and instilling in us a sense of work and responsibility. Life for women in a communist state was difficult and arduous to the point that every woman in those decades deserved to be called a hero.

My mother did only one job all her life, the job chosen for her by the state. As I see her today in her eighties, and how she manages to use all the advantages that technology creates for the provision of information, communication and solutions, I am sad that she didn’t have the opportunity to discover herself and use all her potential.

However, my mother was lucky enough to see her daughters more educated than herself, who did the work they chose to do and not what the state or ideology would have chosen for them, and who managed to face an extremely difficult transition in every sense.

Whereas, for my daughter and two nieces, the spectrum of rights is unmatched and equally unmatched is that of opportunities where they can navigate and live out their dreams and passions. What I described very briefly above has developed in very complex and difficult contexts with large efforts to reach the civilized world while battling daily with our complicated Ottoman-communist past.

Today there are still girls and women writhing in the clutches of this past, just as there is a huge army of girls and women engaged in education, health, social services, justice, arts and culture and up to the highest levels of public administration, governance and policy making. The clear progress and great power of this army makes me believe that all girls and women of the future will have crossed the threshold of submission and will be capable to live the life they chose and not the one chosen for them. Meanwhile, no vision of the future for women can be separated from the vision of the future for boys. The time has come to talk equally about both, the future of girls and boys.

M de C: You share your life with Edi Rama, the Prime Minister, who together with his political responsibilities is also an artist. What is that life like for you?

Linda Rama: Have you ever asked the question, “how does a Prime Minister who is also an artist cope with a wife who is a professor and researcher of public policies and at the same time a civil activist?” To answer your question, I can say that Edi’s political responsibility as the Prime Minister of Albania makes it impossible for our attention to be limited to each other’s coping skills, but to try to make every minute of Edi’s useful for his transformative vision for Albania. Is this hard? Yes, it is hard.

M de C: As all eyes are fixed in Albania, who are the emerging Albanian talent for the arts, cinema, music, literature, theatre, opera, architecture and other creative outlets?

Linda Rama: One can follow the brilliance of Albanian artists around the world to see the potential and creative capacity of this small country. There is Ismail Kadare, Ibrahim Kodra, Ermonela Jaho, Tedi Papavrami, Angjelin Preljocaj, Dua Lipa, Anri Sala, Ermal Meta, Rita Ora, Sajmir Pirgu, Nensi Dojaka, Fadil Berisha, Luiza Gega, the boys of the national football team in Euro2024 or Mira Murati, who, in recent years, climbed to the heights of technological creativity. The stories of these people are as extraordinary as their talent and their achievements are examples that nothing is impossible for the dreamers who are unstoppable to make their dreams come true.

M de C: The EU is said to be the largest provider of financial assistance to Albania. Is this correct?

Linda Rama: This is completely true in terms of financing, and I think that for Europe this assistance is very important for its own policies. You cannot wait for countries like us to survive on their own. It is impossible! So, one of the last studies that I did – which was published some months ago – is a very deep analysis of the fiscal regulations and how to cope with development objectives: where we can find resources, where are the resources that we can use.

That study clearly shows that our ambitions are much higher than our possibilities, and most of the resources now are not within reach of European Union financing or government financing, because the fiscal regulations are very tight even though we would improve efficiency, on whatever we are going to get, we’re talking about a small percentage of whatever is currently the official assistance, because today this is directed towards private capital, foreign and domestic.

To mobilize foreign private capital is not that easy, of course, they share the same objective but it’s not easy and I think that one of the fantastic things that Edi has done since the very beginning is to mobilize – like in architecture, for instance – to find new ways to overcome the bureaucracies that kill investments, and to make the country attractive from investors’ point of view.

Big investments which have been made in tourism – like these well-known architecture projects – most of them are strategic. They are classified as strategic investments. That way you save time, mobilizing and easing procedures to make the investments work. But still the resources are clearly much less than what we need, and, in this way, Europe should be a major contributor. Of course it depends on our capacity to absorb it!

M de C: Once the Albanian dictatorship ended in 1991 at what point did you start engaging with the European Union?

Linda Rama: My first real contact with Europe was, if I’m not mistaken, in 1996. I was invited to a big meeting with this financial think tank of transforming the European Currency Unit (ECU). We were in a big meeting in Hungary, and I remember how passionate and how brilliant the discussions were, it was idealism at work. I don’t find that happening now. Because the generations again have changed. But I think that Europe should, and Europe for us is very important because it’s not our institutions that monitor our progress, in terms of standards, and in terms of the advancement that we must make. Their monitoring is very professional, and we know what’s missing and – if you see the progress reports – you’ll see since 2007 what we have done every year to overcome each step, and that is very important to us.

M de C: Can you tell me more about your Human Development Promotion Center (HDPC)?

Linda Rama: I co-founded HDPC with a colleague of mine who sadly passed away two years ago. From March 1999 to December 1999, I was working for the government. I was leading the privatization agency under the Council of Ministers under the Prime Minister at that time. Then in December 1999, the new Prime Minister that was appointed decided not to work with me, he decided to take me out of the agency. I was a technical person, I was not a political person. I was very young, 34 years old at that time and leading the most important agency in the country, and the most important reforms.

M de C: As a woman and an economist in a post-dictatorship Albania, what challenges did you face?

Linda Rama: I have a background in economics, but I was the first to go and come back in 1993 from abroad with a master’s degree in my field, so I was full of hope. I knew what I was supposed to do: to catch up with eastern bloc countries like the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary that were very much ahead in terms of reforms, also because their past was completely different from ours, they had institutions before they got in the block, like market institutions, and never went to extremes like we did, of full state control without any private entities. They had, of course, more advantages, but I understood very early on that the whole game was the speed and quality of the reforms that would at the same time meet multi-dimensional objectives that in Albania were much more present compared to other countries. But we needed to catch up.

M de C: Did the word ‘privatization’ start to appear in Albania in the early 1990’s?

Linda Rama: I knew when I came back that I was leading a large privatization movement, and a strategic privatization, from my role putting together the legal framework and the regulatory framework. There was also the question of implementing it. I started to understand that politics was very complicated. We shared the same agenda with technical people, the same speed and the same knowledge. To put it simply, I think that people were following different paths, without knowing what to do, how to cope. Winning also was a very important aspect. They wanted more and more to work with their ‘people’, and I was not one of them.

M de C: Did you find your way into politics at the start of Albania’s economic transformation?

Linda Rama: Yes, but I survived three prime ministers within that journey. Aleksandër Meksi was the one from the Democratic Party, he stayed the longest after Edi, and was elected in 1992, and he stayed in power until 1996.

He was also elected for a second term, but then 1997 changed everything, working with the pyramid schemes, financial collapse, and I was working with the government that was to go on and establish normality in the country. The other prime minister was Fatos Nano, the leader of the Socialist Party, So, three prime-ministers. Edi is the fourth.

It’s a lot of political pressure, and privatization was very much a political reform. Then in 1999 I was part of a project in Poland, with Leszek Balcerowicz and Ewa Balcerowicz, his wife. Balcerowicz was the Minister of Finance in Poland at that time, and I think vice prime-minister as well, and they had a foundation, CASE, that was a center for economic and social studies, which was known for bringing experts together from different countries, and I was part of a project with them at that time, I was teaching at the university, financial, international finance, as well as researching, and he was a professor from Stanford University, so I had a certain engagements with different projects abroad.

My intention was very much to see what was happening all the time, and I was also one of the first contributors to Project Syndicate from 1995 to 1997, a platform that is very well known here, and I was one of the four first people, because of my work at the university.

M de C: How do you stay focused on your long-term goals?

Linda Rama: That is a very interesting question. I started, as you know, in economic research, and then I left government and I understood from the start that going very deep into economics was not for me, because you could become very theoretical, and clearly, at that time, that was not our intention. You could not be useful, just going deep into the theory! I was a woman, and I had the children to look after. At that time, Rea was eight years old, and I remember thinking to myself “if I don’t have the strength to face this work-life dilemma, what is it like for every woman around the world who is not in my position, fortunate to be well educated, a fighter, independent, and free?” My father raised me even during Communism to think like a free person, I’m so grateful to him for that, and I thought what is going on. So, I decided that my first mission was not to set aside the question of economics in Albania, but to pursue it. The second mission was to see the economic connections with the human experience and social challenges.

The questions surrounding human rights are very interesting to me coming from a country, from communism, where we didn’t have any rights.

M de C: What is driving the current wave of sympathy for and interest in Albania that is increasing not only in Europe but worldwide?

Linda Rama: In these 35 years of transition, we Albanians have been able to face two historical challenges: to open the world’s doors to us and bring the world to our door.

The first stage began in July 1990 with thousands of Albanians filling the embassies’ yards in Tirana and boarding the ships in Durrës to escape communist isolation and poverty. Then and for many years after, tens of thousands of other Albanians every year took to the mountains, the sea and the air with impatience to live the European or American dream. With enormous effort they succeeded in gaining their right of citizenship in the countries they chose to live in by overcoming mountains and seas of prejudice.

Theoretically, in 1990, together with the fall of communist isolation, Albania also opened its own door to the world. The first to come were the foreign international institutions and also a few foreigners coming for work. Furthermore, for more than a quarter of a century, the only tourists in Albania were Albanians in emigration when they visited their families or Albanians in the region. I remember a conversation with colleagues around 2008. Worried that the world almost didn’t know us or even when we were mentioned in the international media it was because of some wrongdoings here and there across the border, we were trying to find out how to change this image. We talked and talked until one of my colleagues said: “Don’t try to find a solution, the image of Albania will change when Albania changes.”

Albania has changed. Today, Albania is visitable, marketable, livable. The increased wave of sympathy and interest for Albania in Europe and the world is because Albania today offers nature, history, culture, services, sports, entertainment, comfort, adventure, infrastructure, architecture, work and security. In Albania you are safe everywhere and you have no reason to feel unsafe. To bring the world to Albania’s door and to make Albania known in the world, I believe, has been the most unimaginable and the most difficult and painful journey of transition, which has marked also the end of extreme communist isolation. Until a decade ago we continued to be at best a potential, today we are a tourist reality with still much untapped potential. What has happened in the last decade is a tangible product of the development vision of the political leadership and the extraordinary work of Albanians in Albania, and Albanians around the world where they live and work in these three post-communist decades.

M de C: You are a very caring woman connected to the most vulnerable groups in society, what are your motivations and expectations?

Linda Rama: I believe that the way we think, behave and act in relation to vulnerability defines us as individuals and as a society. In Albania, the social structure that we inherited from communism and the rather difficult transition of the past three decades has produced vulnerabilities that even the most economically powerful states would have difficulty resolving in real time. Also, over the years I have understood increasingly that there is a perception that in society the term “vulnerability” refers to the term “poverty”, thus dividing society into “us” and “them”. It is true that poverty is vulnerability, it is a great vulnerability. Sometimes and unfortunately this kind of vulnerability is also inherited through the generations. But I also think that vulnerability is not only exclusive to the poor, even more so in the time we live in, when no one is exempt from the risk of being vulnerable. Therefore, it is in everyone’s interest to cultivate special empathy and solidarity towards vulnerable groups. I also remain hopeful that the Albanian state and its society will guarantee that the next generation of children will not be punished in their journey towards the future by the vulnerability of their parents but will be given support to access all the opportunities available, just like other peers.

M de C: What do you see as the benefits of Albania stepping into the European Union?

Linda Rama: Before the United Europe became a reality, there was the dream that in the same sky and on the same earth, there would be a flag. It was this dream of the founding fathers and the dream of their nations for peace, unity and well-being that created the project of the European Union.

We Albanians have the sky, we have the earth, but we still don’t have the flag of Europe. The dream of owning that flag is perhaps the only dream that has not faded at any moment in these three and a half extremely difficult decades, despite the passage of time and despite the changing of generations. The fact that Albania belongs to Europe remains deep in our common consciousness. And we Albanians know better than anyone what it means not to have that affiliation. We tried harder than most, when we didn’t have it, during half a century of communist dictatorship and isolation, and in 1990, for the first time in history, we chose Europe ourselves and freely as our own destiny when we shouted against the dictatorship “we love Albania like all the Europe”.

Therefore, for us Albanians, the European Union is not a cash cow, but a country like the one imagined by European founders when they dreamed the most extraordinary political project in the history of the world.

M de C: Is Albania on track to join the European Union?

Linda Rama: It’s about belonging and longings. And we talk a lot of belonging, we in fact belong to Europe, and so taking this notion of belonging to Europe, and developing it out, you know, as a philosophy, for countries like us, is very important. We are a country that never ever disputes the fact that it belongs to Europe, and this should not be taken for granted by countries like ours, and I don’t think that the Balkan region is all the same. In this respect we are Europeans, and we are trying to the fullest to go to the level of being well-integrated from the belonging point of view. Because, from a longing point of view, we are already there!

Read also > INTERVIEW. Nicolas Dufourcq – Bpifrance: “We have never granted as much aid to innovation as in 2023”

Featured Photo: Linda Rama’s portrait