In the summer of 1924, Paris once again became an Olympic city. Aside from the medal count, which put France in third place behind the USA and Finland, this edition serves as a model for the Paris 2024 Games. It was in this year that the Olympic Games were given their current motto, while the City of Light was given a superb international showcase.

This VIII Olympiad, which ran for 84 days with its summer session from May 4 to July 27, 1924, already looked much better than the last event held in the City of Light, six Olympiads earlier.

During this edition of Paris 2024, the United States reigned supreme with a harvest of 99 Olympic medals, 45 of which were gold, widening the gap with Finland (38 medals), itself hot on the heels of France (37 medals).

The founding nations of the Games, still traumatized by the bloodshed of the First World War, refused to invite defeated Germany.

A victorious tug-of-war

After the organizational fiasco of the Paris Games in 1900 – drowned out by the programming of the Universal Exhibition – France was finally awarded the precious status of host country for the second time in its history.

This was anything but an obvious choice, given that Amsterdam and Barcelona were the Olympic Committee’s preferred choice over Paris.

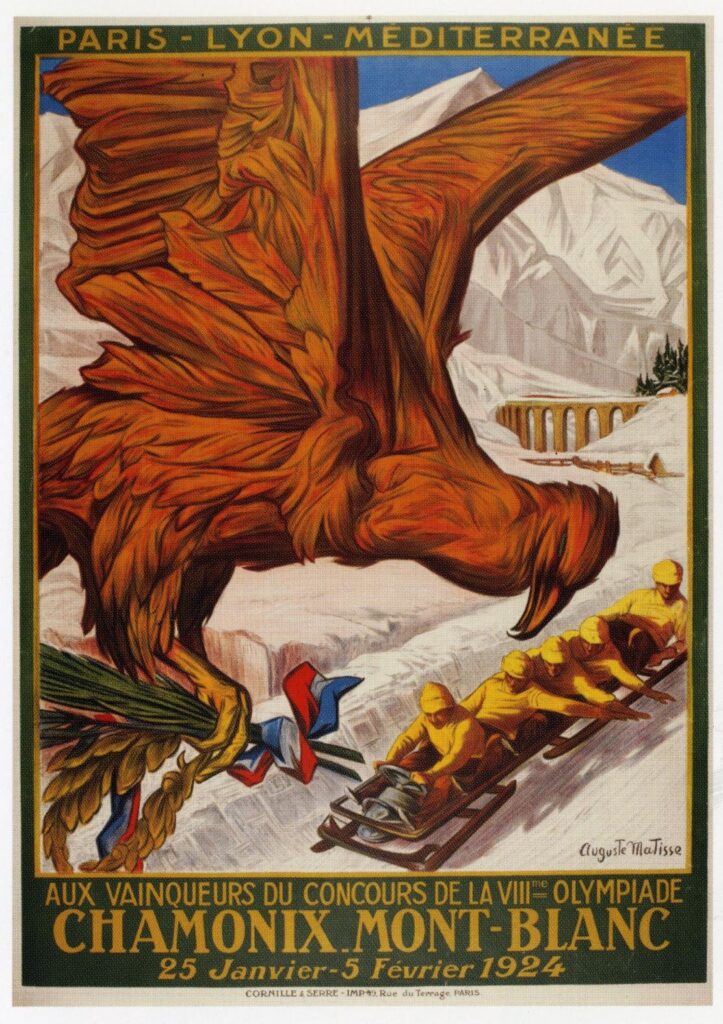

All the more so as France had just organized the first Winter Olympic Games in the same year. Officially dubbed the “Winter Sports Week of the VIII Olympiad”, the Games were held in the host town of Chamonix from January 25 to February 5.

To make matters worse, Paris has no infrastructure worthy of hosting such an international sporting event. Lagging behind its European counterparts, the City of Light obtained the construction of the Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir at Colombes from the Racing Club, with a contribution of 4 million francs (less than initially planned). Entrusted to architect Louis-Faure Dujarric, the building was to replace the existing wooden bleachers.

A model of diversity

For this VIII Olympiad, 17 sports were on the Olympic program for 126 events, during which 3089 athletes competed, including 135 women (i.e. 4.37% of all athletes).

In fact, unlike the 1904 Games, all minorities, colonial populations and specific groups were able to compete. Thus, despite the segregation in force in the United States, African-American athlete William DeHart Hubbard won Olympic gold in the long jump. At 7 m 46, he just missed the Olympic record (7 m 76 by American Robert LeGendre), becoming the first African-American gold medallist in an individual event in any sport.

Endowed withan unprecedented international aura, 44 nations (compared to 29 in the previous edition) choose to take part in the Paris Olympic Games and send their best athletes. Five countries took part for the first time: Ecuador, Ireland, Lithuania, the Philippines and Uruguay.

The live coverage recently made possible by radio attracted almost 1,000 journalists.

While Russia refused to take part in what it perceived as the manifestation of “bourgeois capitalism”, Germany was simply not invited, as the stigma of the Great War was still fresh. Goethe’s homeland was thus the only nation temporarily banned from the Games, as it had been in Antwerp in 1920, alongside Austria, Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria.

The organization of the 1924 Paris Games prefigured the Greater Paris project, with events held throughout the Paris region. The Olympic Village with its adjoining stadium was built in Colombes (Haut-de-Seine), where the opening ceremony took place on July 5, 1924, as well as the athletics, rugby and soccer events.

Rowing was held in Argenteuil, cycling and the marathon in Meudon, the hunting range in Versailles and Issy-Les-Moulineaux, while the polo fields were shared between Bagatelle and Saint-Cloud.

New rituals

The 1924 Paris Games officially gave the Olympic Games their current motto, “Citius, Altius, Fortius” (faster, higher, stronger), put forward by Pierre de Coubertin, who borrowed it from Abbé Henri Didon.

The current format of the Closing Ceremony also saw the light of day, with the unfurling of three Olympic flags: that of the International Olympic Committee, that of the host country and that of the next country to host the Games.

Above all, the Paris Games saw the creation of the very first Olympic Village, built near the Stade de Colombes. It consisted of some sixty wooden barracks, each equipped with three beds. Three meals were provided for the athletes, who shared washbasins, showers and dining rooms. This first Olympic village also offered a number of services to athletes, including a currency exchange office, a laundry service, a hairdressing salon, a newspaper kiosk and a post office.

These buildings were intended to provide direct access to the sports fields, but unlike the Paris 2024 Games, they were not intended to be a permanent facility.

Exclusively reserved for men, it wasn’t until the 1956 Melbourne Games that the Olympic villages finally welcomed women.

Muscle and spirit

It’s a little-known fact that the Paris Games were not intended as an exclusive celebration of sport.

In the purest ancient tradition and in accordance with the wishes of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, President of the Olympic Committee at the time and founder of the modern Olympic Games, the games included artistic events.

The Olympic Games of the Arts, or Pentathlon of the Muses, saw the light of day at the Stockholm Games in 1912. His idea was to design five events around architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture.

Strongly criticized and even shunned by major delegations such as the USA and Oceania, this format disappeared from the Olympic program at the end of the post-war London Games in 1948.

America reigns supreme in the pool

If the United States dominated the rankings at this 8th Olympiad, it was largely thanks to the exploits of its playboy swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, the future Tarzan of the silver screen.

This Hungarian-born, American-born stateless man was also the first swimmer to break the one-minute barrier in the 100-meter freestyle in an Olympic pool, with a time of 58 seconds 6 tenths in 1922.

But it was in July 1924 that Johnny Weissmuller became a legend, at the Tourelles swimming pool, where the 400-meter freestyle was held. Weissmuller was a powerful force, beating Australia’s Boy Charlton and Sweden’s Arne Borg. In the official report, race director Émile-Georges Drigny wrote: “A nautical battle the likes of which are rare and the likes of which may never be seen again”. The American won in the final meters, shattering the Olympic record for the event in 5 minutes and 4 seconds, a record that would stand until 1972.

With his perfect crawl, he also outdid his rivals in the 100-meter race. He even repeated the feat in the 4×200-meter freestyle team final, setting a new world record in the process.

The triumph of the “Flying Finn

The undisputed champion of the track and field at the time, Finland created a stir with the mythical figure of Paavo Nurmi, “the man with the stopwatch”.

The Finn won gold medals in no fewer than five of the world’s most prestigious running disciplines: the 1500 m, 5000 m and 10,000 m individual events, as well as the 3,000 m team event. The undisputed cross-country champion won both the individual and team events.

Of these events, the 5,000-meter race pitting him against Ville Ritola will live long in the memory, the Finn winning in 14 min 31.2 s against 14 min 31.4 s.

The cross-country race was particularly demanding, taking place on the Colombes plain in 45°C shade. It was such an ordeal that 23 of the 38 participants gave up. Nurmi flew through the inferno.

His performance earned him the nickname “TheFlying Finn” from the press. This nickname would later be bestowed on other Finnish Olympic racers of the interwar period, such as Ville Ritola, Hannes Kolehmainen and Volmari Iso-Hollo.

It wasn’t until 2004 that another champion – Morocco’s Hicham El Guerrouj – won gold in four disciplines at the same edition, thanks to a 1500-5000-meter double.

Still in the world of running, the British Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell were crowned champions in the 100-meter and 400-meter events respectively. Hugh Hudson’s film Chariots of Fire retraces their astonishing careers.

Roger Ducret

France won 37 medals, 13 of them gold, but only one name stands out: Roger Ducret.

The 36-year-old fencer won a medal in every event in which he competed (5 out of 6).

At the Paris Games, he won three gold medals (individual foil, team foil, team epee) and two silver medals (individual epee and sabre).

Only Nedo Nadi was able to surpass this feat at the 1920 Antwerp Games. He won gold medals in all the categories in which he competed: individual foil, individual sabre, team foil, team épée and team sabre.

Afine swordsman, Roger Ducret is also a fine writer. During the Games, he wrote for three newspapers: L’Echo des sports, l’Intransigeant and la Petite Gironde. After his sporting career, he became a sports journalist for Le Figaro and L’Echo des Sports.

FencerRoger Ducret was not the only French athlete to shine at the Paris Games. The “Musketeers” of French tennis Henri Cochet, Jean Borotra, René Lacoste and Jacques Brugnon shared silver and bronze medals in men’s singles and doubles.

Finally, France wins its first and only gold medal in water polo.

Read also > Olympic and Paralympic Games: an inclusive and responsible mega-restaurant

Featured Photo: Paris 1924’s Olympic Games official poster, détails © Mairie de Paris