A spice with a thousand virtues, saffron is reaching record prices, while its refined taste is prized by diners around the world. But beyond its prodigious coloring power—100,000 times its weight in water—and its fragrance, this “golden flower,” as it is known in Persian, has been used as an offering to the gods, a culinary condiment, a medicinal remedy, and even a plant-based deodorizer.

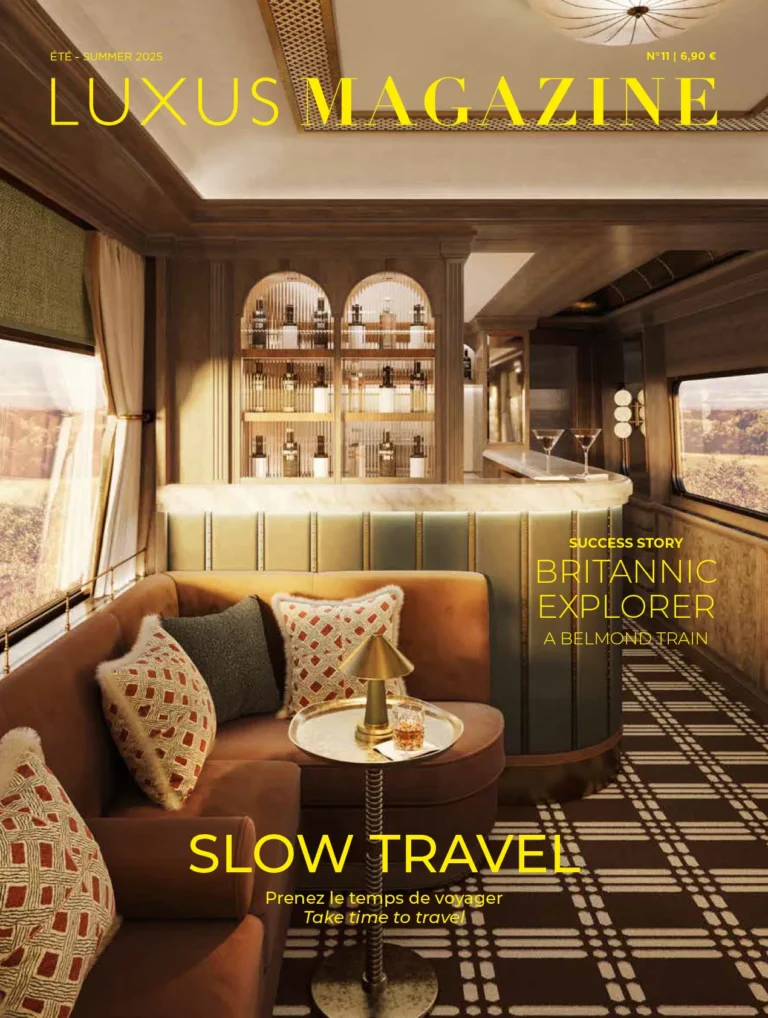

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article, “A Brief History of Saffron,” is excerpted from the print edition of Luxus Magazine (No. 10, Spring 2025).

With a price negotiated between 3,000 and 35,000 euros per kilo in 2020, saffron appears to be the new red gold. However, this spice, with its strong coloring power and hay-like scent, has been cultivated by humans for 5,000 years.

If saffron, “asfar” (yellow) in Arabic and “Zarparan” (golden flower) in Persian, features in the Song of Songs, Homer’s Iliad, and even curbed Alexander the Great’s ambitions in Asia Minor, it is primarily because it is extremely rare.

A miraculous harvest

With its sterile pollen, saffron does not produce seeds and therefore cannot grow in the wild. To cultivate it, its bulbs must be replanted and given constant attention. It needs a rainy spring and a dry summer. Add to this the fact that the plant must be regularly watered but never flooded.

Anyone wishing to harvest its three precious blood-red stigmas, contained in its yellow pistil and as light as air, must also harvest the plant at the right time: its autumn flowering lasts only a few days, with each flower blooming at dawn and wilting at dusk.

Finally, harvesting it is almost a sacred ritual: it takes 140,000 stigmas to obtain one kilogram of this divine coloring agent. Adding to its magical dimension, attested in Egypt by Theban papyri from the 18th and 19th dynasties, its origin remains a mystery.

An origin shrouded in mystery

The original spice is said to have appeared in ancient Persia during the reign of Darius I, around 500 BC in what is now the southern province of Khorasan. While Iran is commonly described as the birthplace of the original variety—the crocus cartwrightianus—a Buddhist legend places its appearance in the 5th century BC in the high valleys of Kashmir, India, thanks to the Mongol invasions.

The spice became one of the main sources of income for Iranian families in Derbent and the mythical Isfahan. Persean saffron threads interwoven in royal carpets and shrouds were found in the capital of the Persian Empire from the 16th to the 18th century. Beyond its original lands, the cultivation of a domestic saffron, Crocus sativus, imported to our latitudes by Phoenician merchants, has been attested in Greece on the islands of Crete and Santorini. Frescoes found at the Akrotiri site are the first botanically accurate representations of the plant. Krokos, the Greek name for both the spice and a village that was once a major center for its harvest, derives from the word “filament,” a direct reference to the long, thin stigmas of its pistil.

A key ingredient in risotto alla milanese, saffron is thought to have reached the Italian peninsula and then Spain via the Muslims in the 7th century.

As for its spread in the West, it accelerated significantly after the First Crusade. The English king Edward III encouraged its cultivation throughout his kingdom, while it brought fortune to the city of Basel (Switzerland). For his fresco in the Sistine Chapel (Vatican), the painter Michelangelo is said to have obtained his yellow pigment from crushed saffron stigmas mixed with white travertine and powdered umber.

Prodigious powers

Used primarily as a natural dye, saffron was used in the making of royal garments, but also in the veils of Roman women, the illuminations of copyist monks in the Middle Ages, and even in the tunics of Buddhist monks. The Babylonian, Persian, and Median kings were among the first to benefit from it, considering the spice to be as precious as purple (a pigment obtained from a marine mollusk, the Murex). In The Iliad, the poet Homer describes Eos, goddess of the dawn, as dressed in her Krokopeplos, or crocus cloak.

Beyond its purely decorative and aesthetic uses, the plant was used in the embalming rituals of women in ancient Egypt, whose bodies were covered with resin and paint made from saffron powder. Homer and Virgil highlight its importance in religious traditions: during the autumn festivals, priests crowned with saffron flowers celebrated the wedding of the god Bacchus, while the flower adorned the temple of Venus.

Queen Cleopatra, like Alexander the Great, is said to have taken baths in saffron milk, known for its aphrodisiac and revitalizing properties. The thermal baths of Rome followed suit, offering specialized therapies. On the advice of Hippocrates and Diocles, saffron was used to cure all kinds of ailments, including eye diseases, earaches, toothaches, and even ulcers. The first written record of the medical use of saffron was discovered in the library of King Ashurbanipal. A veritable medicine in the Fertile Crescent region, it was used to treat vision problems and genitourinary diseases, but also as a tonic and natural antidepressant.

The Romans used it to refresh the skin, treat coughs and relieve the liver. Its powder was used to combat alcohol fumes. Scattered on the ground during triumphal ceremonies (such as the 90 kilos used for Ptolemy’s naval parade), saffron acted as a natural deodorizer in the city, particularly near theaters and banquet halls.

It is said that, since ancient times, saffron has been used in nearly 90 treatments. Its importance, which declined after the fall of the Roman Empire, was revived in the Middle Ages between 1345 and 1350 when the Black Death decimated Europe.

The Persians were the first to use it as a natural condiment. A recipe by the cook of King Zohac mentions the use of the spice in the preparation of veal basted with old wine and perfumed with rose water. The Persians also used it as a dye to color administrative papers and royal decrees.

Long the preserve of the ruling elite, a symbol of spiritual discernment and endowed with medicinal properties, saffron embodies all the ambivalence of our age, which is obsessed with social distinction, the search for safe havens and even spiritual values, and the quest for a healthier lifestyle.

This spice with a thousand virtues is now in high demand on the markets. While Iran produces 80% of the precious powder and India and Spain are in the top three, other countries are looking to carve out their share of the pie. This is the case in Morocco, Azerbaijan, Italy, Greece… and even France, which is developing this microculture.

Article first published in the print edition of Luxus Magazine No. 10, Spring 2025

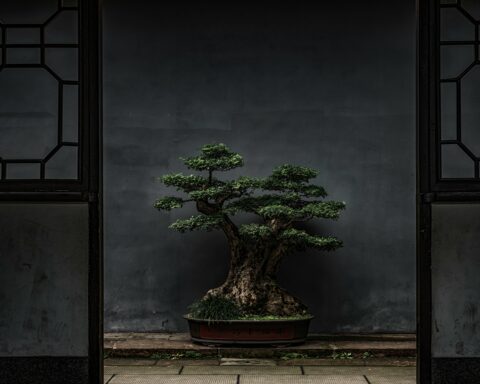

Read also > A brief history of… bonsai

Featured photo: Unsplash