At the beginning of December 2024, sake became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A welcome spotlight for this Japanese rice-based alcoholic beverage, based on a manufacturing process established 500 years ago. While its appeal is growing in Europe, consumption has been steadily declining in Japan since the 1970s. The disenchantment of Japanese youth with this ancestral beverage even seems to have increased post-covid.

This is the story of a drink that is wrongly regarded as a highly alcoholic digestive.

How could this be possible in a population lacking the very enzyme that facilitates alcohol metabolism? Where the Chinese have their baiju – spirits distilled from sorghum-based cereal wine – the Japanese have their sake, made from fermented rice. The former contain up to 50° alcohol, the latter between 13 and 16°.

Deeply rooted in Japanese culture, to the point of having been elevated to the status of national drink, sake was most likely born in China. However, the Japanese have perfected its production, notably through the discovery of an ascomycete fungus.

Sake-making using koji, a kind of mold that transforms starch ingredients into sugar, has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is the archipelago’s 23rd entry on this list, after nôgaku theater, washoku cuisine and local folk dances. Benefiting from the veritable Japan Mania that animates Europeans in search of exoticism and imbued with Kawaii culture – based on anime and manga – since their earliest childhoods in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, sake nevertheless suffers froma continuing disaffection in its country of origin.

Sake is not the only traditional alcoholic beverage to have been recognized by Unesco last December: shochu, a distilled liqueur (made from sweet potatoes, barley, rice, etc.) from south-western Japan, is also present, as are awamori (a traditional alcoholic beverage from Okinawa) and mirin (Japanese rice wine).

Ancestral know-how

Although the term sake refers to the famous beverage and, by extension, all Japanese alcoholic beverages, the Japanese population prefers the term nihonshu (日本酒, literally “Japanese alcohol”), to designate it more specifically.

Initially reserved for the imperial court, sake was also given as a sacred offering to the kami, the Japanese deities. At the heart of Shinto religious rituals, it earned the title of “drink of the gods”.

In the 8th century (Nara period), sake was given its letters of nobility by an edict of the imperial court. The sophistication of its production, thanks to the discovery of a fungus essential to the fermentation process, prompted the imperial palace during the Heian era (794-1185) to create a dedicated department. The department’s task was to ensure strict compliance with production techniques and its use in rituals. It wasn’t until the Edo Era (1603-1868) that the multi-stage brewing technique, virtually unchanged since then, became established.

Similar to “rice beer”, it is made using spring water in which rice is steamed and fermented, thanks to the action of kōji-kin (麹菌, literally “microbe-yeast”), a mold or fungus found in soy sauce and miso. It is this kōji-kin that produces the enzymes that transform rice starch into sugar: “This is a singular brewing process, even on a global scale, called ‘double fermentation’, which transforms cereal starch into sugar, and then this sugar into alcohol ”, explains the daily Nihon Keizai Shimbun.

Hailed by UNESCO, this ancestral know-how has been perfected over the years by toji (master brewers) and kurabito (brewery craftsmen).

Consumption at half-mast in Japan

Particularly rooted in Japanese culture and the Shinto religion, sake is one of the main offerings to the gods, along with rice and rice cakes. Sake is also a part of many rituals, and is consumed at festivals, weddings and family reunions.

Despite this prominent place in Japanese daily life, national consumption of sake has fallen by a factor of four over the past 50 years. In 2023, the Japanese drank 390 million liters, compared with 1.7 billion in 1973. This may be due to lower consumption or even a lack of interest in alcohol among young people, as well as a preference for beer and wine.

The Japanese are therefore relying more and more on Westerners… to make their compatriots drink again. Exports have more than doubled since 2011, reaching 29 million liters by 2023, driven mainly by the USA and China.

Less acculturated to the taste of rice alcohol, Europe – and France in particular – is becoming more and more enthusiastic. As a sign of this craze, exports to France have doubled since 2020.

To appeal to this growing clientele, sake is becoming more floral and fruity (of the Ginjo and Daiginjo type), thanks to the use of particularly polished rice offering a pronounced taste of green apple, lychee or banana. Other players, like the Takara Shuzô sake house, developed Mio in 2011, one of the first sparkling sakes (Mizubasho) on the market. With its low alcohol content (5°) and apple and pear flavours, it has become the benchmark for sparkling sake. Its fine bubbles and, above all, its freshness are said by some to rival champagne. Even more surprisingly, this beverage long considered sacred can be found in creative cocktails and even sorbets.

Meanwhile, true connoisseurs and top restaurants alike are turning to more confidential sakes with more pronounced tastes (aged sakes, kimotos, nigoris or natural sakes). Purists prefer Junmai, rich and intense, to Ginjo and Daiginjo. It is characterized by a pronounced rice taste, marked by umami, that fifth flavor so dear to Japanese cuisine. Unfiltered and cloudy, nigori has a uniquely creamy texture, while its deep taste is reminiscent of oxidative wines.

The trendiest establishments are multiplying the number of food-sake pairings, along the same lines as food-wine pairings.

For some time now, sake has benefited from a strong media presence in France, and as many seductive operations, whether with the Salon Européen du Sake, launched in 2013, or Saké Nouveau, launched in 2018 by the founder of the Maison du Sake. But it’s above all the Kura Master competition for traditional Japanese spirits (sake, Umeshu, Honkaku Shochu and Awamori), initiated in 2017, that has put the sacred beverage on the map in France. A new phenomenon when you consider that the first establishment specializing in sake in Paris dates back to the early 2000s.

Read also > A brief history of… the French aperitif

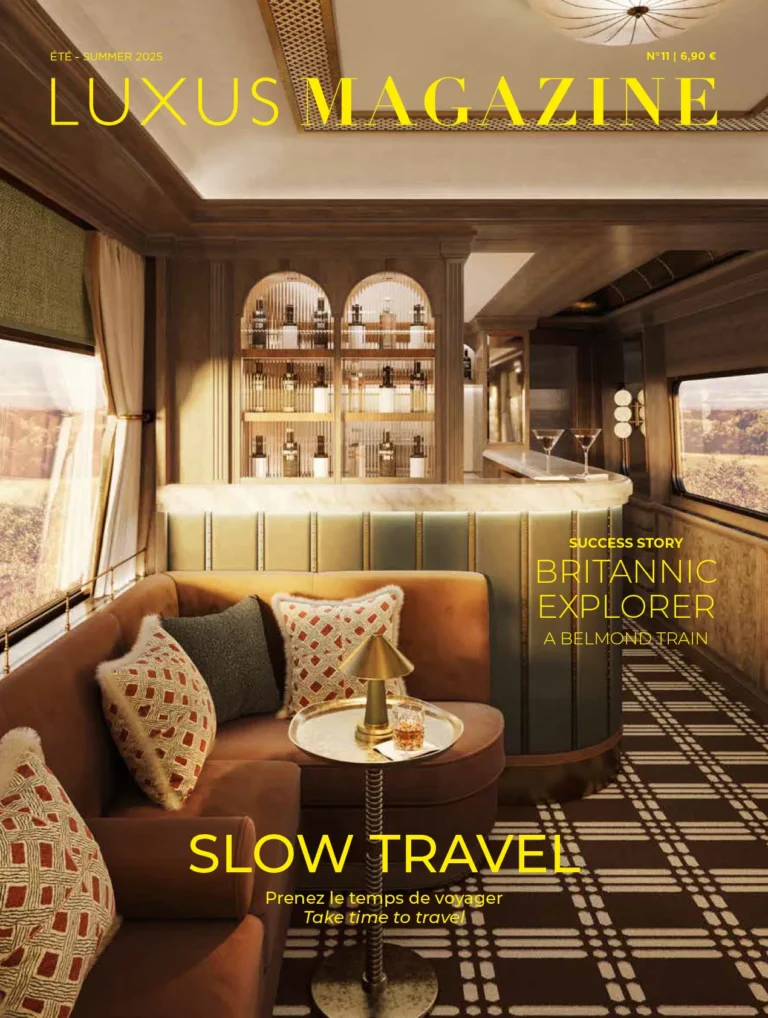

Front page photo: Unsplash