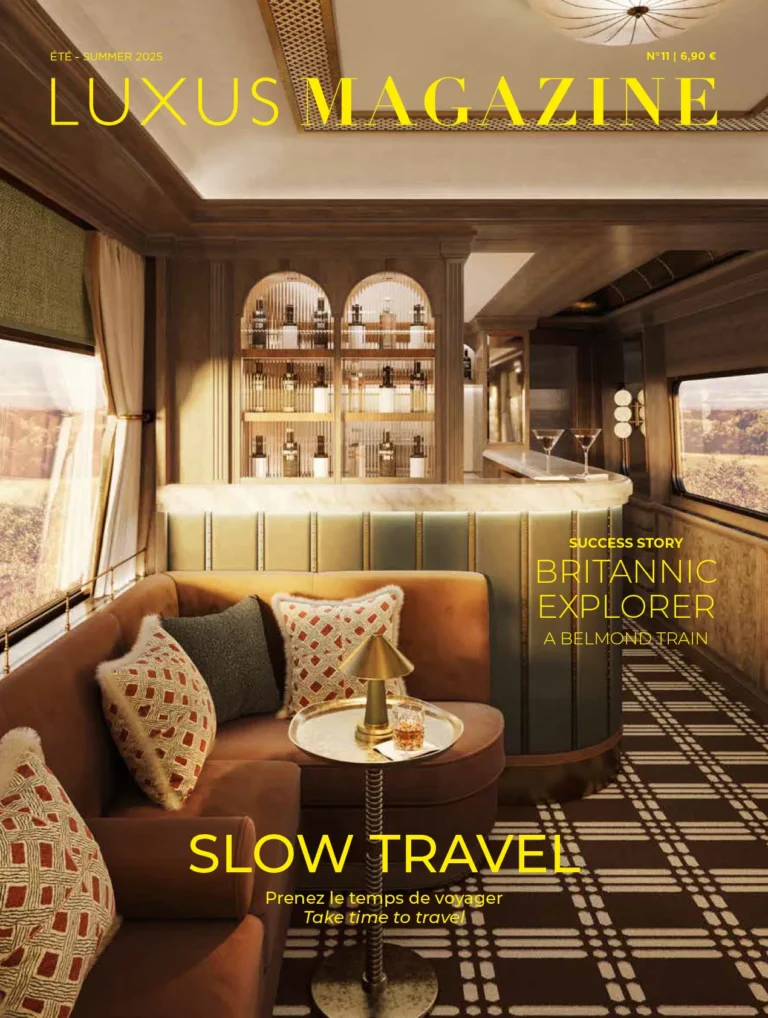

Le Comte de Monte Cristo, the new French blockbuster by Alexandre de La Patellière and Matthieu Delaporte – screenwriters on the last successful adaptation of Les Trois Mousquetaires – is one of the best start-ups of the summer season. Behind this literary and cinematic success, the ambivalent figure of the Comte, in search of lost happiness and consumed by the idea of taking justice into his own hands, continues to fascinate. Here’s how.

Released on June 28 – a Friday, so to speak – The Count of Monte Cristo has already sold over 3 million tickets in its first two weeks! The film’s success is also reflected on the Tiktok social networking site (1,400 publications to date about the film) and in bookstores.

According to the Syndicat des libraires, sales of Alexandre Dumas’ masterpiece increased fourfold between June and July 2024, compared with the previous year. According to Blanche Cerquiglini, publisher and head of the Folio classique collections, Gallimard expects sales to increase tenfold during the film’s theatrical run.

But beyond the film’s success in theaters, what explains the attraction of this story, which is much darker than that of The Three Musketeers? And what if the key was to be found in its hero, or rather its anti-hero, Edmond Dantès, prototype of the superheroes that Marvel and DC Comics would later spawn?

A timeless injustice

The figure of the Count of Monte Cristo resonates with key themes in today’s public debate, such as distrust of the elite and justice in particular, the fascinating and corruptible power of money, the definition of friendship, the fight for equality and against injustice, or even more luminously, the quest for happiness and the compelling need for self-fulfillment.

For thebook, published in the summer of 1844, begins where Walt Disney and company prefer to end their stories: with a happy ending. Edmond Dantès, first mate on the ship Le Pharaon, has a brilliant future ahead of him, both professionally (he’s just been promoted to captain) and romantically. Not to mention the fact that, in addition to true love (with Mercedes Herrera), Edmond Dantès has three very good friends (Danglars, Fernand Mondego and Gaspard Caderousse)… or so he thinks.

But when he’s arrested on his wedding day, he’s falsely accused of a Bonapartist plot to overthrow the restoration of royal power embodied by Louis XVIII. It seems that his loyal companions, suddenly consumed by jealousy, vanity and concupiscence, found his meteoric rise intolerable.

Thrown into the impenetrable gaols of the Château d’If, off the coast of Marseille,in February 1815, he brooded from the depths of his cell over his bygone glory days. Nevertheless, he found a faithful companion in Abbé Faria, an erudite priest. On the brink of death, Faria entrusts him with a priceless secret: the location of a fabulous treasure on the Italian island of Montecristo, off the coast of Corsica. Following a perilous escape through the depths of the sea, fourteen years after his imprisonment, he managed to reach the mysterious treasure island.

Now considered dead, this Count of Monte Cristo, rich in millions and hiding under assumed names, will never stop tracking down the traitors and taking methodical revenge on each and every one of them. Each of them, moreover, accumulates undeserved responsibilities and favors within the financial, political and military powers. Not to mention the fact that one of them has managed to win the heart of his beloved.

Despite his dark intentions, the Count of Monte Cristo will find grace along the way , and come to the aid of people who would otherwise have met an unfortunate fate. The masked avenger, motivated by resentment alone, proves to be a good Samaritan.

An eerily similar story

If this infamous story is rich in detail, making it easier to identify with the young man who is struck down in mid-air, it’s because the character of Edmond Dantès is loosely based on a true story known as “The Diamond and the Vengeance”, which was already published in an undoubtedly fictionalized form in 1838.

Instead of the naval officer, Pierre Picaud (a name which, however, has every reason to derive from the author’s imagination), a “chamber cobbler” from Nîmes, is about to marry the beautiful and very wealthy Marguerite Vigoroux. But one of his “friends”, Mathieu Loupian, a cabaret owner and widower with two children, has his eye on Marguerite’s dowry.

When Pierre comes to him to order a wedding feast for twelve, Loupian bets that he’ll delay the party with the help of a commissioner, a regular customer. With the help of two of the bar’s customers, Solari and Chaubard, he falsely accuses Pierre Picaud of being a spy and a royalist agent in the pay of England.

Arrested like Edmond Dantès on his wedding day and taken away in the greatest secrecy, Picaud was locked up for seven years in the no less impenetrable Alpine fortress of Fenestrelle (today in Piedmont, Italy, where the legend of the Man in the Iron Mask is said to have originated) without knowing the reason for his arrest.

During his imprisonment, he befriended a detained Italian priest, Father Torri. A year later, Father Torri died and bequeathed him a treasure hidden in Milan.

Old and frail, Picaud took the name Joseph Lucher. He seizes the treasure and plots revenge against his former friends. Disguised as a clergyman, he passes himself off as a certain Abbé Baldini and meets up with an old acquaintance, Allut, in Nîmes, who, in exchange for a large diamond, tells him the story of his denunciation motivated solely by jealousy.

On learning that Loupian had bought himself a café on Boulevard des Italiens with the dowry of Marguerite Vigoroux, whom he had married two years earlier, Picaud stabs Chaubard and ruins Loupian: an alleged Prince of Corlano seduces Loupian’s daughter, knocks her up and asks for her hand in marriage. On their wedding day, Corlano sends a bill to each of the 150 guests revealing that he is a former galley slave. The family is disgraced. The drunk Loupian son is found at the scene of a burglary and sentenced to twenty years hard labor, while the Loupian café is set on fire. Solari is found poisoned.

A transformative role

For what is now at least the fiftieth interpretation of Edmond Dantès, the co-director had one sine qua non condition: to entrust actor Pierre Niney with the role of this sunny, vulnerable man changed by captivity.

A role full of nuance, that of a man constantly torn between good and evil.

On the set of TF1’s 20 heures, the French actor declared, “In my personal life as an actor, and even in my intimate life, there was a before and an after to this shoot. It’s a crazy adventure”.

To immerse himself in a character intended by the directors as “charismatic” and “mysterious”, the actor revealed in the film Yves Saint Laurent worked as usual to music, listening to the grandiose and enigmatic orchestrations of Max Richter, world-renowned notably for his epic interpretation of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (2012).

“Giving your body and soul to roles like this, I think it’s the minimum courtesy, already for the spectators, because it’s an incredible work,” declares the 35-year-old actor, adding, “It explores the best of man and the worst of man, the darkest.”

Filming was a marathon affair, with “iron discipline” including forced weight loss. Far from being a constraint, “it helps to embody characters as rich and complex as Edmond Dantès”, confided Pierre Niney.

Embodying the character required hours of preparation, if only for the make-up (over one hundred and fifty hours). The actor had to accompany his character as he aged and changed his clothes. The transformation was such that his parents wouldn’t have recognized him on screen!

In fact, the filmmakers opted for a metamorphosis using real on-screen masks in the style of American superheroes, something unheard of in the many adaptations of this literary classic!

Except that the Count is no Bruce Wayne or Robin Hood, as co-director Matthieu Delaporte explains. “Monte Cristo is not a Robin Hood. He’s someone who has all the money in the world, but he doesn’t give it away. He dedicates it to his revenge. He’s a totally modern hero in this individualistic, selfish dimension.”

Read also > The Three Musketeers: a French blockbuster full of flair

Featured Photo: © Chapter 2 – Pathé France