The central beverage of Roman society, from slaves to patricians, wine – and above all its taste – has remained a mystery to researchers. A recent discovery published in the archaeological journal Antiquity may well shed light on its characteristics, based on its packaging.

“In Vino Veritas” (“In wine, the truth”), wrote Pliny the Elder.

However, until now, the dress, texture and, above all, taste of the wines consumed by the Romans 2,000 years before our era, had mainly come down to us through the accounts of ancient poets.

At the end of January, researchers Dimitri Van Limbergen of Ghent University (Belgium) and Paulina Kamar of Warsaw University (Poland) may have solved this impenetrable mystery.

To achieve this, the research duo came up with the unusual idea of resurrecting ancient vessels (dolia), replacing them with contemporary terracotta models that most closely resemble their shape. In their view, these containers have a decisive impact on the character of wine.

Dolium in the domus?

Archaeologists tell us that wine cellars, housing earthenware vessels, were particularly widespread in the late Republican and early Roman Empire (between the 3rd and 2nd centuries AD and the 3rd or 4th century).

Among them was the dolium (plural dolia), a large earthenware jar (can hold over 2000 liters) used for fermentation, storage and transportation of products such as wine.

To recreate the taste of Roman wine, researchers had the idea of replacing these ancient containers from archaeological digs with qvevris, traditional ovoid jars narrower than the body, still used in Georgia for wine production and storage.

In Rome, terracotta containers were buried in the ground, perhaps even in most houses (domus). According to the study, the narrow base of the dolium enabled the grapes to be separated from the liquid, while the pots were then buried up to the neck, facilitating fermentation, just like Georgian qvevris.

The aging process produced sotolon. This aromatic chemical compound has a distinct odor and flavors usually found in curry or roasted nuts. These fermentation methods also gave the wine an orange color. What’s more, the terracotta of the dolia gave the wine a dry mouthfeel, particularly appreciated by the Romans.

In fact, by varying the shape of the dolium, the level of burial and the duration of fermentation, it is possible to obtain a wide variety of flavors, smells and colors.

For example, the four colors identified by Pliny the Elder are albus (pale, white), fulvus (reddish yellow, tawny, amber), sanguineus (blood red) and niger (black).

Wine: an integral part of the meal and the city

From Pliny the Elder to Petronius to Diodorus of Sicily, many Roman authors have recounted the rich history of Roman wine, superstar of the convivium (grand banquet).

Indeed, in Ancient Rome, wine was an integral part of Roman culture, daily life and economy.

Although the Romans were heavy drinkers by modern standards (between 0.7 and 1 liter a day, according to a study by André Tchernia), this beverage from the vines had to have a lower alcohol content.

In addition, the vinification methods used for white and red wines were identical: the grapes were crushed and the skin and softness preserved.

The Romans did not hesitate to cut their beverage with water – whether cold or hot – pure wine being considered a barbaric practice. One part wine to two parts water meant they could drink wine with breakfast.

As well water was likely to be contaminated, wine acted as an antiseptic gouleyant. After fermentation, they also added honey, medicinal herbs and spices.

Wine aging was already a sign of prestige. The most famous grape variety of the time, Falerne, a highly alcoholic, oxidized white wine, was highly prized by the Roman aristocracy and required 20 years of fermentation.

For the Romans, wine remained the centerpiece of the meal. This contrasted with the habits of the Greeks, for whom wine was enjoyed on the side.

This was not the only notable difference with their distant cousins: unlike the Greeks, who placed wine under the patronage of Dionysus (Bacchus in Rome), the Romans preferred it to the king of the gods, Jupiter (Zeus for the Greeks).

This characteristic shows that the uninhibited drunkenness advocated by Bacchus was particularly unpopular. So much so that until the early days of the Empire, the consumption of wine by women was strictly regulated, as it was thought to encourage adultery.

All these practices call into question the cliché of the Roman orgy…

Finally, under the Empire, wine became a democratic beverage, consumed equally by men and women, young and old, rich and poor.

Read also > MOËT & CHANDON: 280 YEARS OF FESTIVE BUBBLES

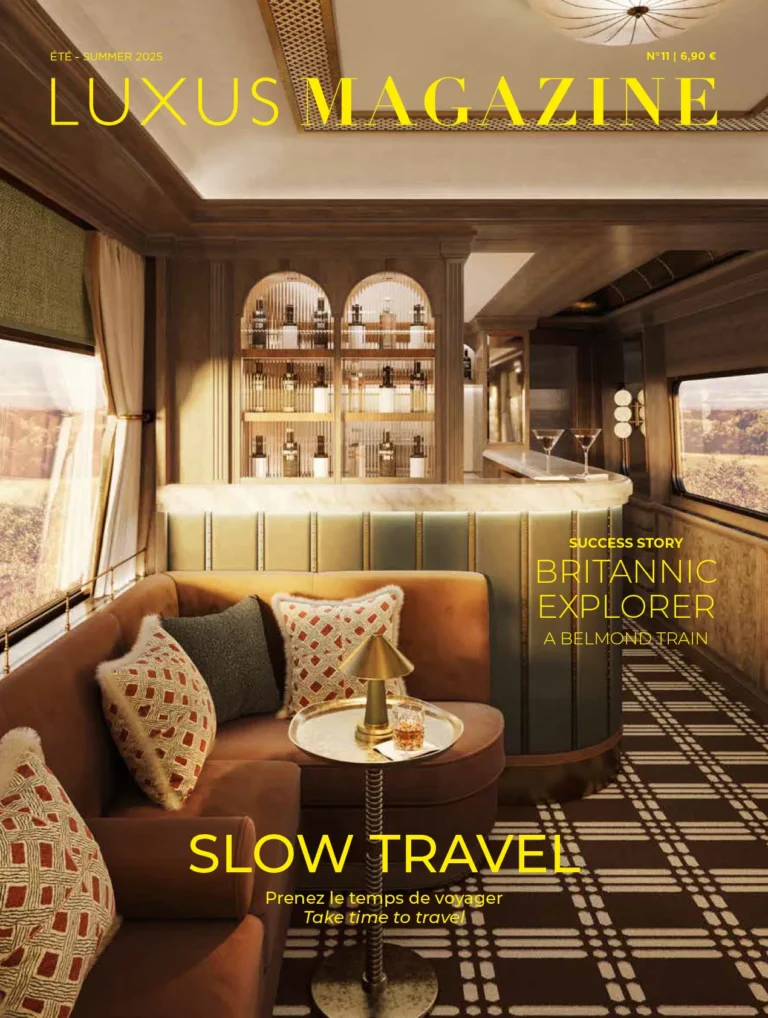

Featured Photo: Ancient Roman fresco of the “House of Menander” in Pompeii