The European elections in June 2024 saw the rise of nationalism and populism on the Old Continent. In the face of economic, social and political crises, far-right parties are gaining in popularity by advocating protectionism and euroscepticism. This rise poses major challenges to the cohesion and democratic values of the European Union.

In the last European elections in June 2024, the far right consolidated its position by sending over 180 MEPs to the European Parliament. Eurosceptic and nationalist parties gained ground in the majority of member states, notably in France and Austria.

Since the 2000s, Europe has witnessed the rapid rise of far-right parties, characterized by their populism and Euroscepticism. This trend has been particularly marked in Italy, Hungary, Poland, France and the Netherlands, where these parties have gained in popularity and often succeeded in coming to power, thus influencing the European political landscape.

The rise of the far right in Europe has been marked by a number of significant electoral breakthroughs. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, which has been in power for over a decade, consolidated its position with an overwhelming majority in the 2022 elections, winning 59% of parliamentary seats thanks to strong support from rural areas.

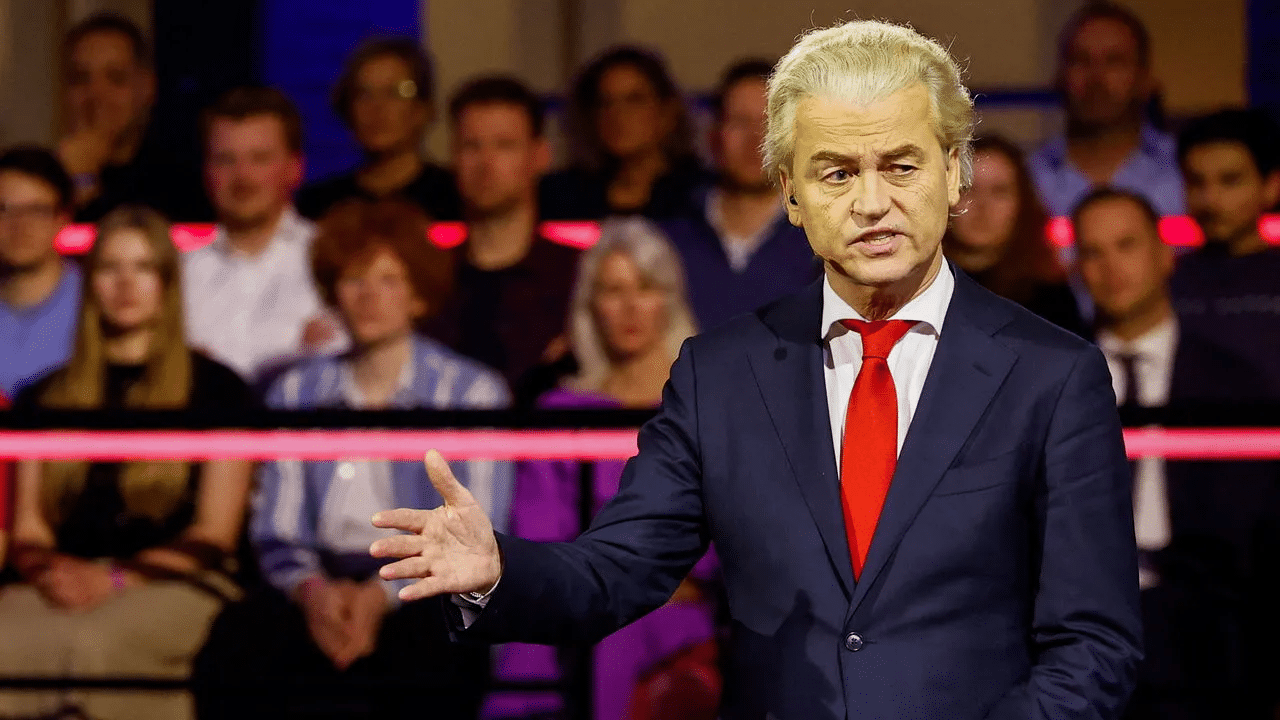

Portugal saw the Chega party (in French: Ça suffit) make a historic breakthrough in 2024, securing over 18% of the vote in the 2024 legislative elections. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders‘ PVV, often dubbed the “Dutch Trump”, won 37 seats in parliament in November 2023, illustrating a continuing rise of the far right in the country.

In Poland, the Law and Justice party (PiS) came to power in 2015 and remains a central player despite a slight drop in support in the 2023 general election, while in Sweden, the Sweden Democrats became the second-largest party in terms of votes in the 2022 general election, with strong support among less-educated voters and rural areas.

A meteoric rise

While far-right parties first enjoyed electoral success in the 1990s, several factors explain this breakthrough.

“It’s a reaction to economic globalization and the crisis of political representation, a distrust of traditional political parties perceived as powerless,” explains Nonna Mayer, a political science researcher at Sciences Po’s Centre for European Studies. During the 2010 decade, cyclical factors were added to this, such as “the 2008 recession, the 2015 refugee crisis and the Islamist terrorist attacks”, adds the specialist.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine triggered an energy crisis and high inflation, reducing the purchasing power of many citizens.

These crises also accentuated inequalities between rich and poor. Between 2017 and 2021, the poorest 1% of French people saw their standard of living fall by 0.17% a year, while the richest 1% saw an increase of almost 3% a year. In Germany, a study revealed that the lower a person’s income, the more likely they are to develop populist tendencies. Thus, an increase in poverty could lead to a rise in votes for the far right.

Back to the future

Far-right parties in Europe share several key characteristics: assertive nationalism, pronounced social conservatism and strong opposition to immigration. They are often critical of the European Union, perceiving it as a threat to national sovereignty. In 2022, almost 60% of Rassemblement National supporters in France considered the EU to be detrimental.

Far-right parties emphasize themes such as restricting immigration and security, attracting an electorate concerned about these issues. In France, the Rassemblement National captured 37% of the working-class vote in the 2022 legislative elections, reflecting particular discontent among the socially disadvantaged.

“The rise of the far right is explained by a fear of change on the part of some citizens, who are trying to return to a past that no longer exists,” says Daniel Freund, a German MEP and member of the Les Verts group.

Thierry Mariani, MEP for the Rassemblement National and member of the European Parliament’s Identity and Democracy Group, disagrees. “This vote is not about going backwards, but about not giving up everything to the future. This push by national parties is about citizens who believe in Europe, but who want Europe to respect their identity and their history.”

A desire to defend morals

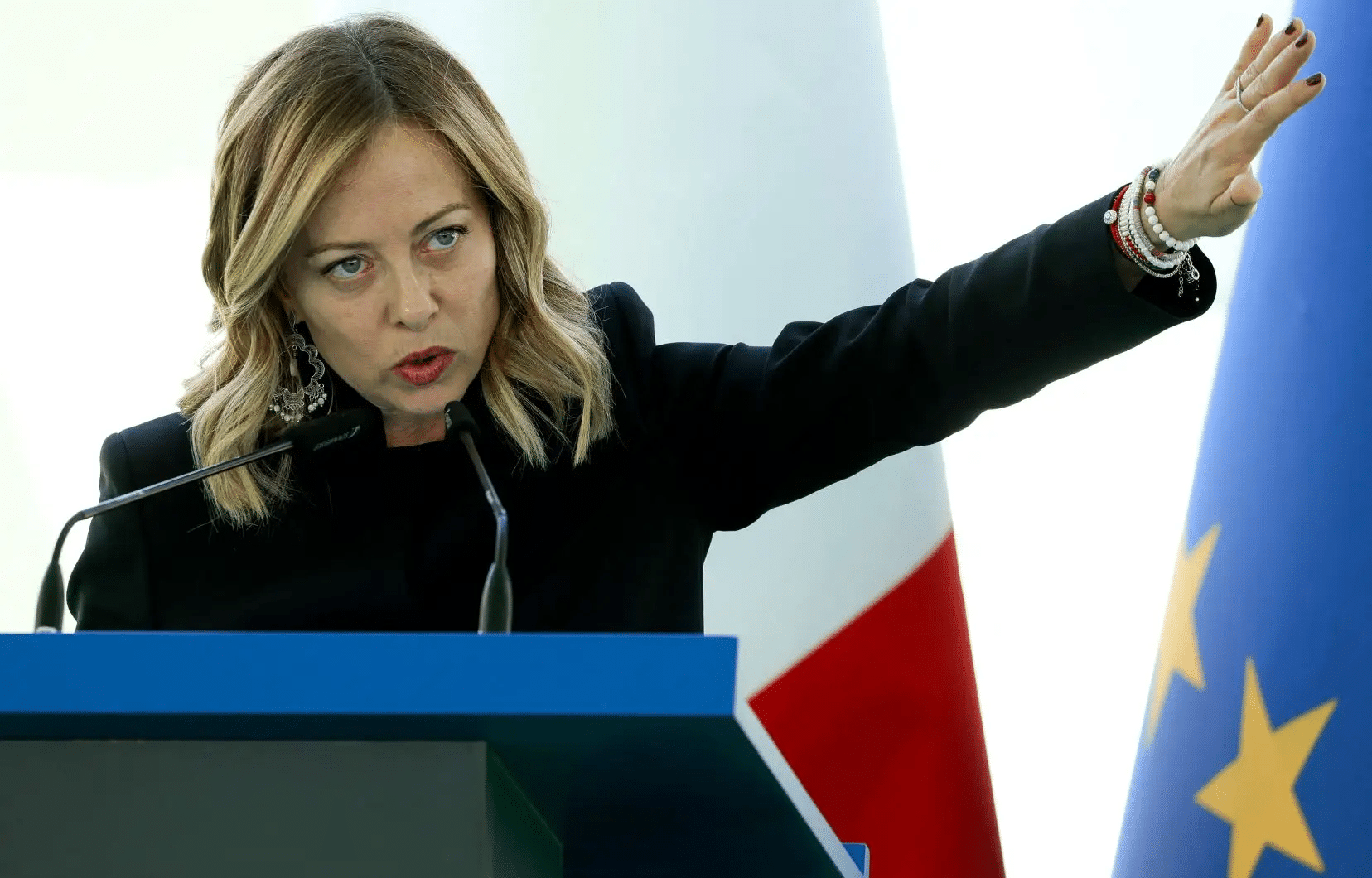

These parties also defend traditional values, particularly with regard to the family model, which implies fewer rights for LGBT+ people. In Italy, the Meloni government asked mayors in 2023 to stop automatically transcribing the birth certificates of children born through surrogate motherhood (GPA) abroad, and this directive has been extended to children born through medically assisted procreation (PMA) by female couples.

Women’s rights are also under threat under far-right governments, which are seeking to restrict access to voluntary termination of pregnancy (VTP). In Poland, abortion has only been permitted in cases of rape, incest or if the mother’s life is in danger since 2020. In Hungary, a 2022 decree even obliges women to listen to the fetal heart before they can have an abortion.

“While these radical right-wingers share authoritarianism and nationalism, they also have different economic and cultural values,” explains Nonna Mayer. In Hungary and Poland, “the radical and populist right-wingers take a very conservative line on morality, which is not that of Marine Le Pen, but rather closer to that of Marion Maréchal. And they are more economically liberal.”

Democracy hit hard

The rise to power of the far right poses risks for democracy and civil rights in Europe.

Countries such as Hungary and Poland, led by far-right parties, have seen their democracy index and press freedom decline, according to several studies. What’s more, these parties can hamper European cooperation on crucial issues such as climate change, with Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen openly criticizing international environmental policies.

Following the 2024 European elections, far-right parties have strengthened their presence in the European Parliament. They often defend national sovereignty and oppose majority decisions in the European Council, advocating the retention of national vetoes on certain strategic issues.

Danger to the economy?

What about their economic programs, often described as suicidal? A recent study published in the American Economic Review on the world economy points out that “populist governments have negative consequences for the economy”.

Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick and Christoph Trebesch of the Kiel Institute examined 1,500 governments in 60 countries between 1900 and 2020, identifying 51 cases of populism. They define populism as a political strategy in which leaders divide society between virtuous “the people” and corrupt “the elites”.

Their study shows that under populists, such as Netanyahu, Duterte, Erdogan, Maduro, Modi, Morales, Zuma, Orban, and Trump in 2018, GDP per capita growth is 0.6 points lower per year than under governments with a different economic policy. After 15 years, this difference reaches 1 point of GDP per capita each year, illustrating “populist economic stagnation”. Note that public debt is 10 points of GDP higher after such a reign.

Populists often fail to improve living standards by prioritizing short-term growth and ignoring inflationary risks. “To implement the ‘will of the people’, populists tend to weaken institutions, limit minority rights, change constitutional and electoral rules in their favor, and repress political opposition,” the researchers point out.

This dynamic creates a vicious circle in which the weakness of democratic institutions fuels a continuing deterioration in the economy.

The rise of nationalism and populism in Europe reflects a complex reaction to recent economic, migration and social crises. These political movements have transformed the European political landscape, posing significant challenges to cohesion and cooperation within the European Union.

Featured photo : © Drawing by Luis Granena, published in the Financial Times