After nearly fifty years of relative silence, the Made in France cloak and dagger film is reborn from its ashes, thanks to Martin Bourboulon’s blockbuster The Three Musketeers. The treasures of our heritage are used here to serve the literary epic of Alexandre Dumas Père marvelously. This will reinforce the attractiveness of the filming locations, such as the Château de Fontainebleau and the city of Troyes.

The rebirth of the cloak-and-dagger film

After the modern but scripturally dubious American adaptations of Peter Hyams’ D’Artagnan (2001) and Paul W.S Anderson’s The Three Musketeers (2011) or the British BBC series The Musketeers (2014), French cinema deserved to have a say again in this masterpiece of national literature.

More generally, it was time for France to take possession of a film genre with a heritage value: the cloak-and-dagger film. A variation of the adventure film that made the very rich hours of French cinema, especially in the years 1950-1960, with the productions of André Hunebelle and Bernard Borderie. The cloak and dagger film, brought up to date by Hollywood, has since reached the top, whether it be the Star Wars saga and its lightsaber battles or the Pirate of the Caribbean saga. In five films, the latter saga incorporating fantasy elements cost $1.145 billion to produce. But it also earned $4.51 billion at the global box office, making it one of the most lucrative film franchises of all time.

In its initial version, the cloak-and-dagger film features period costumes, foil duels, and a chivalric spirit with a touch of comic impertinence, all set in real and mostly historical settings.

The Three Musketeers is among the most emblematic films of the genre. In serial form, published in 1844 in the magazine Le Siècle, the original novel has a sense of rhythm that has nothing to envy to our contemporary series. Whether in the way the author portrays his characters or skillfully uses flashbacks and plot twists, everything is done to keep the reader on the edge of his seat. Exceptionally popular, the story of these companions crossing swords to foil a plot that could overthrow the Crown and plunge the kingdom into war has been adapted to film thirty times since 1909.

But no version, according to moviegoers, has so far managed to dethrone George Sidney’s 1948 film with Gene Kelly as D’Artagnan and Lana Turner as Milady. However, with so much success, it is difficult to renew the idea through a 36th adaptation without distorting the rhythm of the original text.

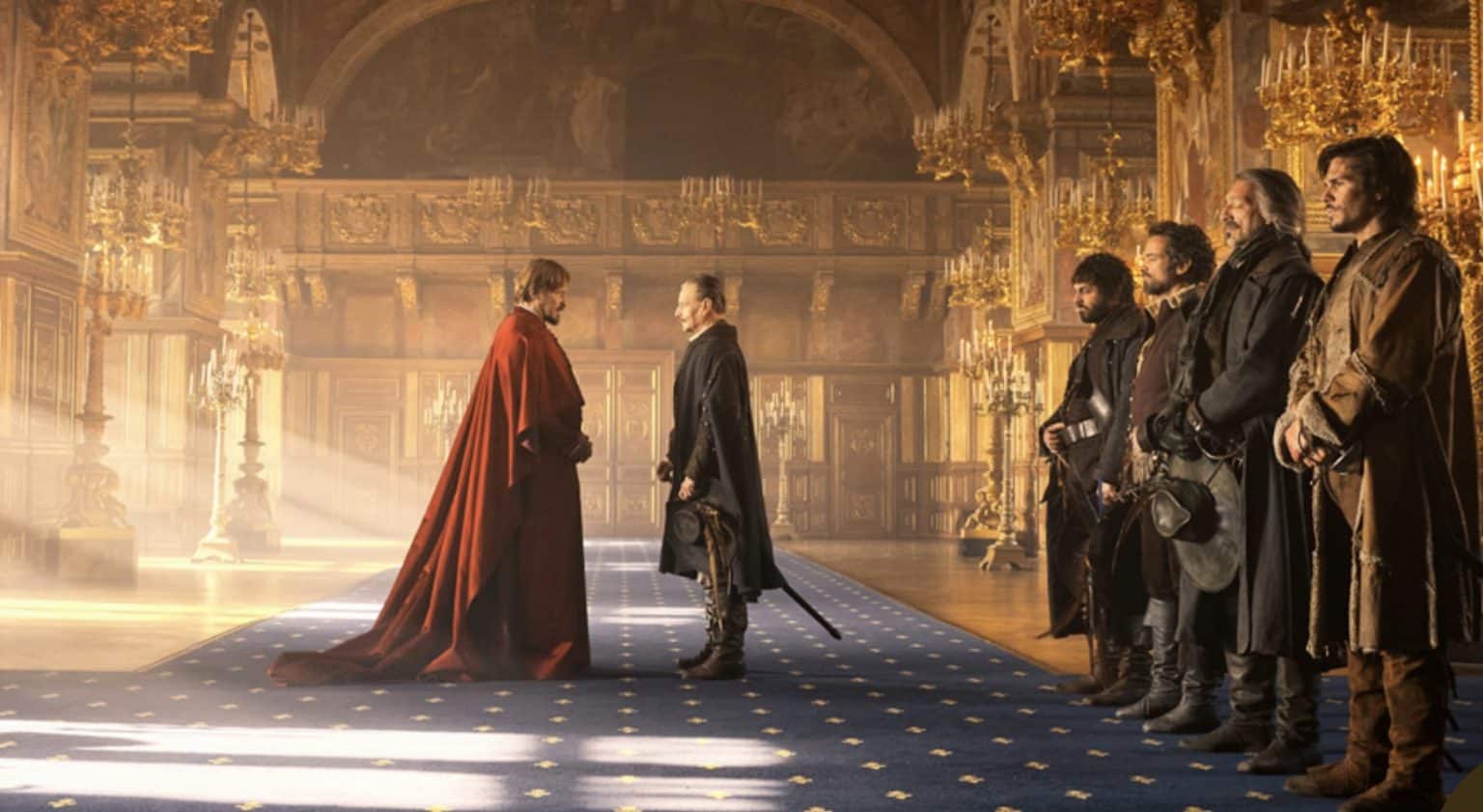

For his adaptation, in two parts, director Martin Bourboulon has chosen to offer a great spectacle and to modernize the codes of the cloak and dagger film through visual elements from the Western and film noir.

One of the novel’s successes is its colorful characters full of flair, particularly its Gascon hero, once filmed as a charming boaster with unparalleled audacity and courage. The interpretation of François Civil shows, on the contrary, a D’Artagnan more voluntary and sensitive than laughing and boastful. At his side, we find a high-flying cast with Vincent Cassel (Athos), Pio Marmai (Porthos), Romain Duris (Aramis), Louis Garrel (Louis XIII), Eva Green (Milady de Winter), Vicky Krieps (Queen Anne D’Autriche), Lyna Khoudri (Constance Bonacieux) or Eric Ruf (Cardinal de Richelieu).

The royal couple formed by Louis Garrel and the Luxembourg actress Vicky Krieps stands out, with a performance marked by subtle restraint and sensitivity to the skin.

The other special mention goes to Eva Green, who lends her features to Milady de Winter, the spy with the appearance of a femme fatale, in the pay of the cardinal. Less frivolous than usual, she appears here as a powerful woman, far from the simple villain of the story.

With a record budget of 72 million euros for the two parts, this new adaptation is part of a strategy of resistance to SVOD platforms (Netflix, Amazon Prime …) consolidated by an alliance between Pathé and Logistical Pictures. The objective is to break free from the financing constraints of the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée (CNC) and to open up to private investors so as to be able to produce more French films with an international scope.

And this begins by revisiting the country’s history in contrast to what the Americans have done.

The other side of the Grand Siècle

Historically, it is customary to link the blossoming of French luxury to the reign of Louis XIV and to a period presented – not without grandiloquence – as the Grand Siècle.

However, contrary to a widespread idea, this period extends well beyond the reign of the Sun King, starting from the reign of his predecessor, Louis XIII, until the end of the Regency (1610-1723). Historians still consider a period one of the most chaotic and unhealthy in French history.

In his modernized adaptation of The Three Musketeers, director Martin Bourboulon, does not forget to depict the era with more realism and less kitsch. In order to correct even the anachronisms of the original author, the director also relied on the secret correspondence between Louis XIII and the Cardinal of Richelieu.

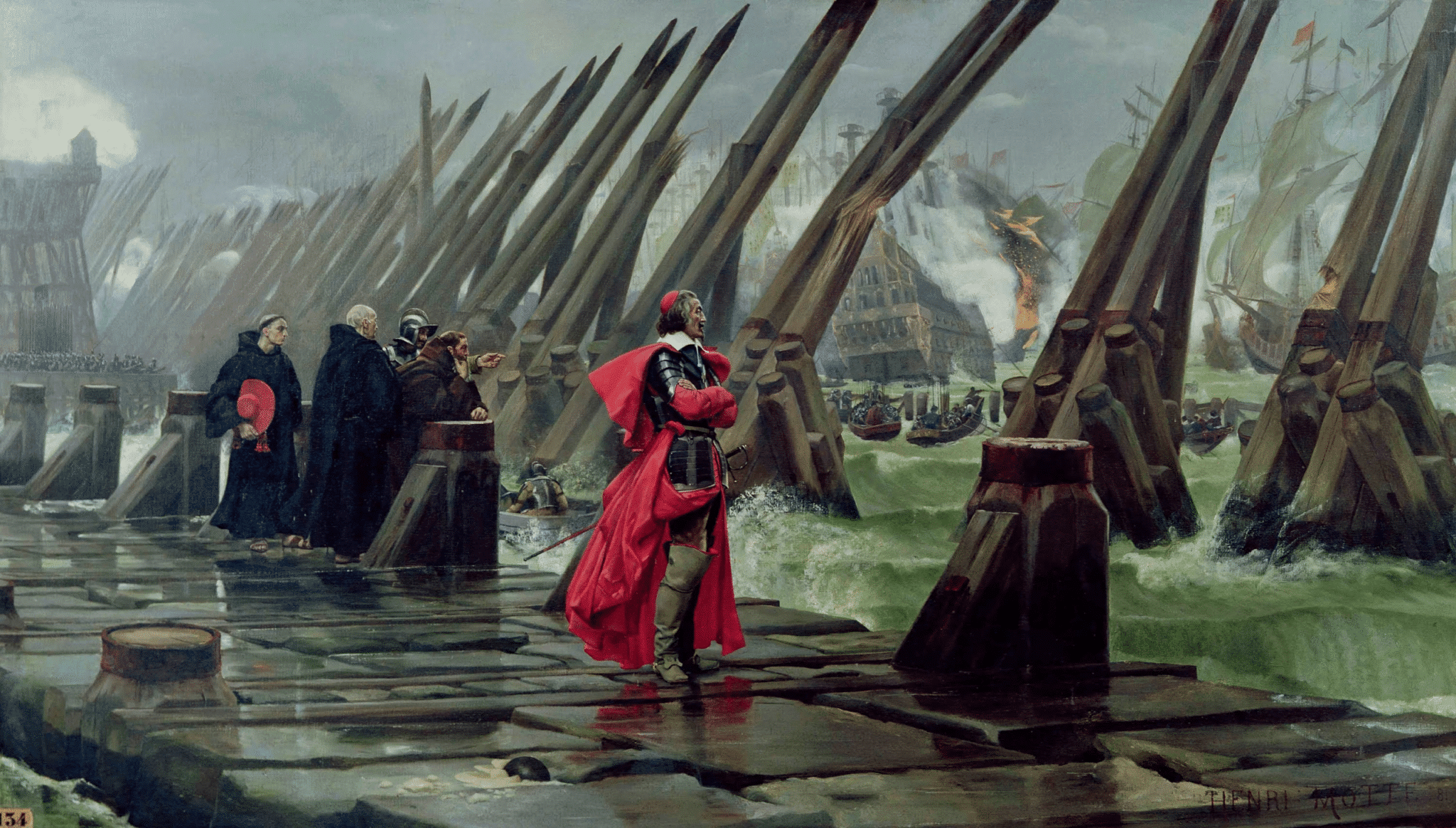

The film opens in 1627, the year in which the siege of La Rochelle begins, and the raising of the famous wooden dykes spread over 1.5 km. This victory of the cardinal two years later on a Protestant stronghold – reputedly impregnable – will strengthen the royal power and will prepare the ground for the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV.

The Grand Siècle was also marked by the wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants, where the smallest alley or palace corridor could be fatal. This oppressive atmosphere is perfectly captured by Alexandre Dumas in his other literary masterpiece, Queen Margot (1994), which has already been adapted for the screen by Patrice Chéreau.

To capture the characters’ constant struggle in the underworld of Paris and its suburbs, the battle scenes were shot in sequence, handheld, offering a subjective view like a video game. To the point that the viewer is as disoriented by the events as the heroes themselves are.

Add to this an omnipotent cardinal minister, increasingly able to compete with the royal power, and the threat of an English invasion by sea, and you get the Kingdom of France on the verge of implosion.

The photography’s patina contrasts with the shimmering hues of the previous adaptations, a sign of the chaos that reigns, even at the state’s highest levels. Dirt creeps onto faces and fabrics while musket shots become more insistent. Nevertheless, magnificent monuments emerge, all the more beautiful because they are the places described in the novel.

The heritage in majesty

A faceless character has always inhabited the cloak-and-dagger film’s exceptional architectural heritage.

The film was shot entirely in France, highlighting some forty monuments, including castles, manors, and abbeys, and in particular, the corsair city of Saint-Malo, which was used to embody the beleaguered city of La Rochelle, which had been abandoned because of the “visual pollution” associated with its modernity. Thus, twenty scenes out of the eighty that make up the saga take place there.

The first part of this saga gives pride of place to the regions of Île-de-France, Seine-et-Marne, and Burgundy. Thus, the Paris of the 17th century comes back to life through the emblematic places of the capital (the square courtyard of the Louvre Palace, the Hôtel des Invalides) as well as in the cobbled streets of Troyes (Aube) and its colorful half-timbered houses. Among the places of interest of the city of Troyes present on the screen, let’s mention the Maison de l’Outil et de la Pensée Ouvrière, a real 16th-century jewel box.

A few miles from Troyes stands the castle of La Cordelière, in Chaource, with its neo-Gothic façade. The place is the scene of the first confrontation between D’Artagnan and Milady.

The Royal Palace, meanwhile, is complemented by scenes shot at the Château de Fontainebleau and the Town Hall in Levallois.

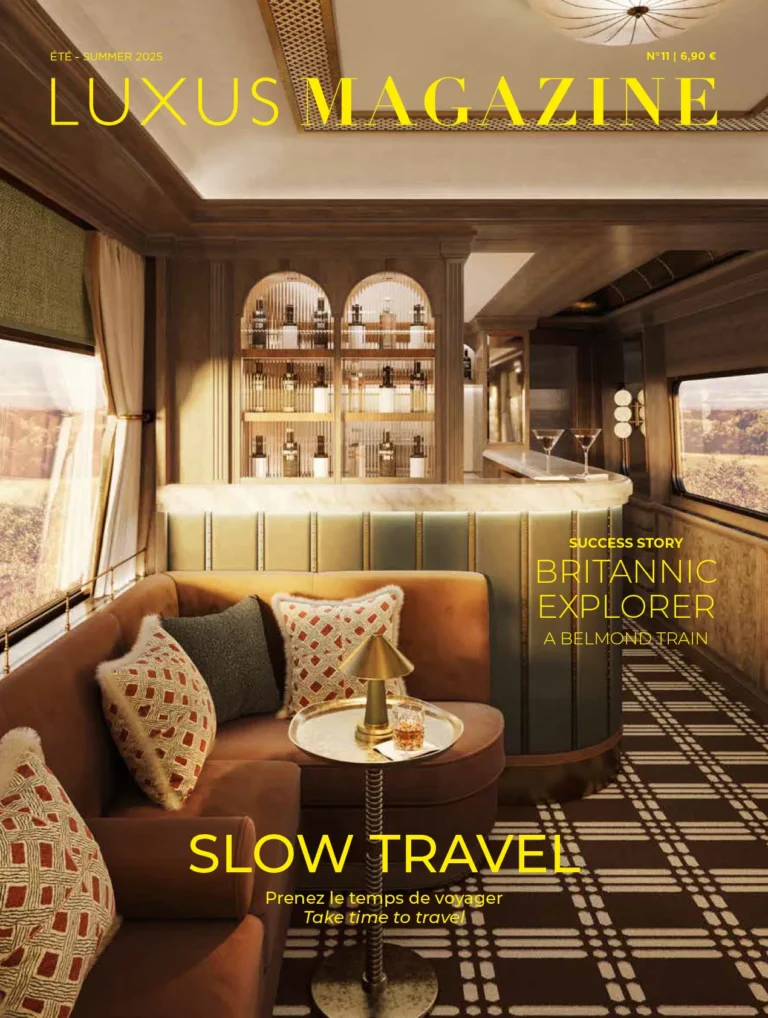

The castle of Fontainebleau, built in the 16th century and the historic residence of King Louis XIII, thus hosted for the fourth time the shooting of an adaptation of The Three Musketeers. The ballroom, with its rich coffered ceiling covered with lunar emblems and the royal motto, was transformed in the film into a throne room (see front page photo).

In addition, the peaceful setting of the Cistercian Abbey of Royaumont became the scene of the forbidden romance between the Queen of France and the Duke of Buckingham, while the cathedral of Saint-Etienne de Meaux, hosted the wedding of Monsieur, the King’s brother, Gaston d’Orléans.

Scheduled to be released on December 13, the second part of the film, entitled The Three Musketeers: Milady, will take place in Normandy, Brittany, and the Centre region. Apart from Saint-Malo, the film will show other exceptional places, such as the castle of La Fontaine Henry (Calvados) as the residence of the musketeer Athos or the castle of Farcheville, an authentic medieval fortress (Essonne).

Director Martin Bourboulon has warned that if the film succeeds, a third part, entitled The Man in the Iron Mask, may be released. In the meantime, the new film adaptation of this literary masterpiece, which has been released in seventy countries, has attracted 750,000 spectators in France in four days.

Read also > 76TH CANNES FILM FESTIVAL : RUBEN ÖSTLUND NAMED PRESIDENT OF THE JURY