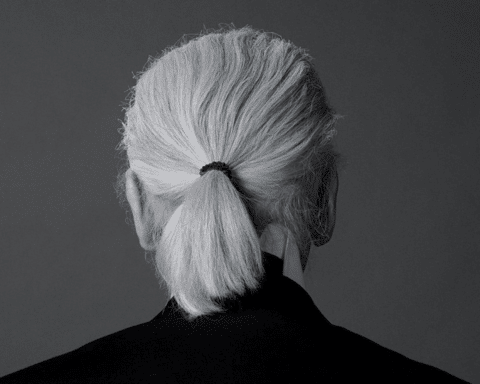

A veritable global muse of the Belle Epoque, everyone wanted to see, approach or even touch this “sacred monster”, against whom no stage – from classical theaters to 5,000-seat circus tents – could resist.

As talented as she was gifted with the fiery temperament of her “devil’s hair”, Sarah Bernhardt was as famous in France as she was on all five continents.

This extraordinary fame prefigured that of the global superstars who would follow her, such as Joséphine Baker and, closer to home, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Beyoncé and Taylor Swift.

The exhibition at the Petit Palais, in honor of the centenary of his death, closes this August 27. It’s an opportunity to get up close to 400 works and objects that belonged to this polymath artist, who was also an actress, painter, writer and sculptor.

A play of fate

Sarah Bernardt’s life is very much like Cinderella’s, or From Rags to Riches as the Americans call it: born into a miserable home, only to die in a blaze of glory.

Nothing predestined this courtesan’s daughter – who worked in a brothel – to take to the stage and become the “Divine” Sarah.

But fate had a hand in it, and her only experience of tragedy was on stage.

Her audiences particularly appreciated her acting, excelling in classic plays (Shakespeare, Rostang, Dumas fils, Wilde…), and her ability to “give herself death like nobody else” in front of a crowd of stunned admirers, from Paris to New York, via Lima and Saint Petersburg.

The authoritative tragedienne used to say “if you don’t do what I want, I’ll stop dying”.

The world owes her dramatic studies to an acquaintance of her mother’s, the Duc de Morny – half-brother of Napoleon III.

Her studies at the Conservatoire, followed by her arrival at the Comédie Française, soon revealed an innate talent that would later prompt Mark Twain to say: “There are five classes of actresses: the very bad, the bad, the good, the very good and Sarah Bernardt.”

After a number of minor roles, she achieved success in 1872 with two plays: Les Passants, in which she cross-dressed, and Ruy Blas, in which she played the Queen of Spain. It was then that the author of the second play, a certain Victor Hugo, gave her the nickname of “voix d’or” (golden voice), the actress being, according to him, one of the few to make him cry.

A member of the Comédie Française, she soon became dissatisfied with the roles she was given. She took things to a whole new level when she slapped a member of the company who had jostled her on stage.

After the commercial failure of L’Aventurière in April 1880, she slammed the door on the institution with “verve et fracas”, publishing a letter of resignation in the press that bordered on insolence: “This is my first failure at the Comédie Française, and it will be my last”.

Sued for wrongful breach of contract, she was ordered to pay Le Français one hundred thousand gold francs in damages.

Returning to her mother’s home, she became a courtesan herself for a time to support herself, before returning to the stage.

Freed from her obligations to the Comédie Française, with the help of her impresario Edward Jarrett – whom she had met in London – she embarked on a pharaonic tour of the five continents, which the media were quick to cover.

Such was her success that the Comédie Française called for her return.

Tired of playing for others, she finally bought the Théâtre de la Renaissance in 1893, where she once again performed her greatest roles, before setting her sights on the Théâtre des Nations in 1899, which she renamed Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt.

Between 1899 and 1914, she performed some forty roles, from Cleopatra to La Dame aux Camélias, Tosca and Théodora.

Scandalously ahead of her time

What first struck contemporaries of her time was her independence, which was out of the ordinary for her time, as she multiplied her famous lovers (Victor Hugo, Napoleon III, Georges Clairin…) and refused the dictates of society. This feminine Dom Juan was a feminist before her time.

In love, as in her work, Sarah was guided first and foremost by passion.

She wrote: “I’m not made for happiness. I live on ceaselessly renewed emotions, and I’ll live that way until my life runs out.”

To capture the imagination and maintain her myth, La Bernhardt relied on a nascent innovation, photography, pioneered by Félix Nadar.

La Grande Sarah used poster advertising to promote her image on tour, signing an exclusive six-year contract with Alfons Mucha, a leading figure in art nouveau.

She soon realized that there’s no such thing as bad press, only good publicity.

Associating her image with consumer products, she was one of the first brand ambassadors.

She shocked the world with her morals and manners, wearing make-up in public – making lipstick a legend – or pants, a practice forbidden to women of her time.

A free spirit, Sarah Bernhardt refused deterministic labels. Presenting herself as both an artist and an actress, she never failed to irritate the bourgeoisie, who would not tolerate the mixing of genres.

Finally, she fascinated her contemporaries with her taste for the bizarre, mixing glamour and the morbid. Thus, when she welcomed her tubercular half-sister into her home, she left her bed to sleep at her feet in a coffin.

Politically committed, she didn’t hesitate to support the anarchist Louise Michel, or to take up the cause of Alfred Dreyfus or the Communards during the Paris Commune.

During the siege of Paris, she transformed the Odéon theater into a military hostel.

Finally, Sarah Bernhardt was also a pygmalionne, helping to promote the talents of artists such as painter and sculptor Louise Abbéma.

Triumphant world tour

Sarah Bernhardt’s singular career was also due to her XXL tours of five continents: Europe, Africa (Egypt), the Americas and even Australia.

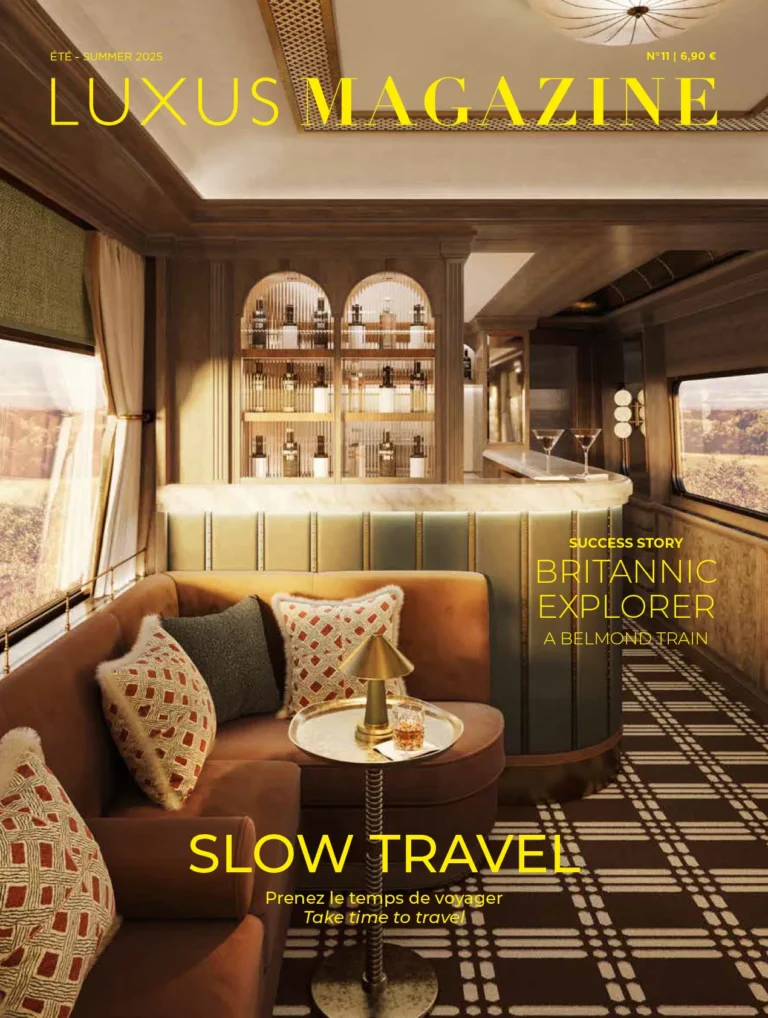

To reach her venues in more or less ephemeral infrastructures, she swallows up the kilometers aboard her personal Pullman Palace train, taking with her 42 trunks of toiletries and personal effects.

She was not alone on her journey, supported by her two maids, two cooks, a waiter, her butler and her personal assistant, Madame Guérard.

Everywhere she went, she was greeted with the sound of the Marseillaise, particularly during her first American tour in 1880, becoming the personification of France. Thus, the tourist of the time, visiting Paris, only wanted to see “two things: the Eiffel Tower and… Sarah Bernhardt.” She thus came to embody the myth of the Parisian woman at the height of the Belle Époque.

Her first tour was a veritable marathon: 157 performances in 51 cities. In New York, she played Scribe’s Adrienne Lecouvreur at the Booth Theatre to an audience that had paid a hefty $40 for a ticket – a considerable sum for the time, especially as most of them didn’t speak a word of French. During this period, she crossed the United States and Canada, from Montreal and Toronto to Saint Louis and New Orleans.

In some places, theaters could not always accommodate compact crowds, so circus tents with a capacity of 5,000 had to be erected!

The press of the time reported that in New York, men threw their coats on the floor to be trampled by the actress, or that she spent three hours signing their shirt cuffs.

And what about the cowboy who travels over 400 km just to see her perform in Dallas?

Bringing back a trunk, filled with $194,000 in gold coins, she tells her friends, “I crossed the oceans, carrying my dream of art, and my nation’s genius triumphed. I planted the French verb in the heart of foreign literature, and that is what I am most proud of.”

She would return to American soil eight times until 1916. In the latter year, she campaigned for the United States to enter the war against Germany, returning to France on November 11, 1918.

Excessive in her commitments and choices, she was also successful in her exit: her funeral attracted more people in Paris than Johnny Hallyday. On March 29, 1923, a million people crowded between her Paris home at 56, boulevard Pereire (17th) and the Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Here again, Edmond Rostang, the friend and playwright behind some of her greatest roles (notably L’Aiglon), could not be more wrong when he declared during her lifetime: “And what a way she has of being legendary and modern!

Read also > BEYONCÉ VS TAYLOR SWIFT: A TOURING DUEL AT THE TOP!”.