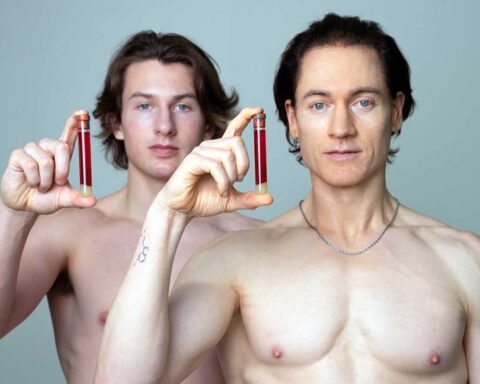

Their names evoke an opulent and grandiose era. That of the Industrial Revolution taking over from the Wild West, of gigantic neo-colonial mansions lining the Hudson River, of New York’s first skyscrapers…And of personalities who, above all, prefigured those who would later be called the great captains of industry and even the founders of GAFAM.

Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Carnegie, JP Morgan…Embodiments of the American dream, these self-made men from rural America made their fortunes by revolutionizing the daily lives of millions of Americans through mass industry.

But in this world of the HNWI before its time, gentlemanly behavior didn’t matter, as long as you won a total victory over the competition.

110 years before Reagan’s ultra-liberalization, the Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Carnegies and JP Morgans built American capitalism.

This is their story, made of steam, oil, steel and, above all, dollars!

America, too, has its Old Money

Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Carnegie and JP Morgan. What remains of these four names, apart from a few namesake buildings such as the gigantic Fifth Avenue shopping complex, Rockefeller Center, the legendary Carnegie Hall concert hall and a powerful Manhattan investment bank? Monumental portraits of their respective wives adorned with the finest jewelry by Cartier, Tiffany’s and Van Cleef & Arpels? Sumptuous mansions, such as Cornelius Vanderbilt’s gothic Biltmore Estate, the largest house in the United States with 250 rooms?

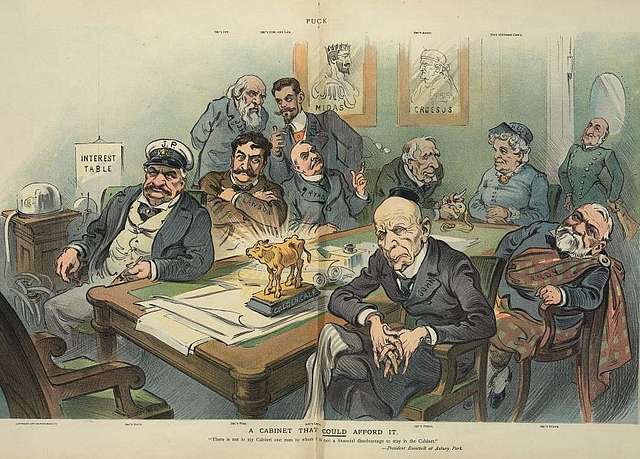

Today, while JP Morgan Chase remains a household name and Gloria Vanderbilt a perfume brand in disuse, only Rockefeller has entered the vernacular, to the point of replacing the expression “rich as Croesus” with his fortune and his title – stainless in the collective unconscious – of America’s first fortune.

While Ralph Lauren has been fantasizing about an American aristocracy through a preppy aesthetic since the 1970s, and Francis Scott Fitzgerald recounts the vicissitudes of the great families of the 1920s in their very posh suburb of East Eggs, outrageously shocked by a parvenu named Gatsby, these made-in-the-USA dynasties are well and truly rooted in the country.

The most emblematic of these Old Money companies surfaced on the other side of the Atlantic, long after the Gold Rush, on the ruins of the fratricidal Civil War.

An early financial culture

One of the common features of these “titans” of the Gilded Age – the period of post-Civil War reconstruction from 1865 to 1901 – is undoubtedly that they developed a real taste for profit at an early age.

Most of these aspiring tycoons, the offspring of large families from modest, rural backgrounds, left school at an early age to work and support their parents.

While John Pierpont Morgan, a banker’s son, learned the rudiments of the profession from his parents and prestigious studies in Switzerland, the others learned on the job. Sometimes through counter-examples, as alcoholism raged in the country.

John D. Rockefeller learned from his father, who sold “miracle” products at fairs to cure all kinds of illnesses, including cancer. This sinister character, who was conspicuous above all for his absence and his willingness to squander the household’s meagre resources, was to leave his mark on the young Rockefeller, at least in terms of his immorality and cruel lack of empathy.

From an early age, Rockefeller set his sights on becoming a businessman. His first modest earnings came from raising turkeys, and from interest-bearing loans to his classmates when he wasn’t selling them confectionery.

Andrew Carnegie, a Scot from Dunfermline, was forced to emigrate with his family to the United States. His father, a linen weaver, had lost his customers to the development of the steam engine. All his life, he kept in mind his mother’s favorite saying: “Take care of every penny, and the pennies will take care of themselves.”

Arriving in Pennsylvania at the age of 10, he was forced to work in a small cotton mill, winding yarn twelve hours a day, six days a week. But Carnegie soon demonstrated an uncommon intelligence and was entrusted with the company’s account book.

In 1851, his uncle recommended him for a telegraph position in Pittsburgh. Gifted with an exceptional capacity for memorization, at the age of 16 he became secretary and young protégé of Tom Scott, then Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Taking him under his wing, he learns the business of management.

No bad profits

With these four industrial magnates, there’s never a crisis, only an opportunity to do business.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, some of the titans capitalized on their speculative culture, to the point where Vanderbilt, known as the Commodore – the Captain – was branded “the most reprehensible of war profiteers” by the press, without being bothered.

During the conflict, he didn’t hesitate to sell old, virtually unusable ships to the Northern government. Once the war was over, these profits were reinvested in railroad shares, notably in the Hudson River Railroad. By the end of the war, Vanderbilt’s fortune was estimated at $68 million ($75 billion today), and he became – for a time at least – the richest man in the United States. During the war, he lost his favorite son George Washington, which led him to turn to spiritualism.

Morgan, on the other hand, has started to invest in arms sales, buying obsolete rifles to refurbish them and resell them at a higher price to the US army. Except that the equipment remained defective. Scandal broke, the government refused to pay and twice took him to court.

As for John D. Rockefeller, he avoided conscription by paying substitutes, being able to afford the $300 required.

On April 9, 1865, the American Civil War ended with the surrender of the South at Appomatox, and five days later Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

The stage was set, with Rockefeller starting out in food brokerage, JP Morgan and Vanderbilt in shipping, and Carnegie in railways.

JP Morgan made his fortune in a most unusual way: transporting migrants to Staten Island, with seven out of 10 boats belonging to his shipping company. Owner of a yacht, the Corsair, Morgan in turn became the captain for the caricaturists of the day.

Winning at all costs

The secret of these titans of the American Gilded Age lies in their ability to surround themselves with the right people and make the most of their connections close to the circles of power. Above all, they knew how to diversify their activities so as never to lose the race for progress.

Noting the development of the steam locomotive, Cornelius Vanderbilt didn’t hesitate to divest himself of his maritime fleet in favor of trains.

By this time, insufficient production capacity to meet inflationary demand meant that competitors had to be absorbed, even by unorthodox means.

To kill off the remaining competition, Vanderbilt, now a rail magnate, went so far as to impose, in 1888, the closure of his Livingston Avenue Bridge, the only access route to New York, the country’s main port.

This episode, which saw the share prices of rival companies plummet, enabled him to acquire railways one by one for a song. Starting with the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway.

Vanderbilt reigned unchallenged from New York harbor to Chicago, and between 1899 and 1900 built a building to his glory: Grand Central Station.

Vanderbilt may own 40% of the rail market, but it lacks the continent’s most valuable line, the one between Chicago and New York, owned by the Eerie Company.

To capture it, he embarked on a massive share buyback, a kind of aggressive takeover before its time. This strategy was soon slowed down by a forged issue of new shares designed to dilute Cornelius Vanderbilt’s holdings. Vanderbilt was swindled out of $7 million ($1 billion today)!

After laying rails across much of the continent, Vanderbilt realized the benefits of transporting goods, and in particular a revolutionary raw material: kerosene.

Thanks to kerosene, American homes could now be lit by oil lamps after dark. This electricity fairy was of great interest to John P. Morgan, who was one of the first to invest in it.

Vanderbilt, seeking to gain a foothold in eastern Ohio, the country’s main oil-producing region, wanted to work with a willing oil well owner on the verge of bankruptcy.

He set his sights on John D. Rockefeller, 27, a gifted but – wrongly – malleable man.

In 1862, shortly after the discovery of a deposit in Titusville, Rockefeller bought out his outgoing partner’s shares in his brokerage business for $72,500 and invested in drilling.

First summoned by Vanderbilt, he narrowly escapes certain death by missing his train and emerges with the conviction that he has a destiny. When the two men meet, it’s a hardened and confident Rockefeller who knows that the golden age of railways – which has lasted for 25 years – is coming to an end. The multiplication of lines had led to market saturation, causing the railways’ share price to fall drastically. Rockefeller negotiated an exclusive agreement with Vanderbilt: to deliver $1.65 a barrel, a third less than the market price. In exchange, Vanderbilt demands 60 barrels a day. Rockefeller could barely keep up with half the production.

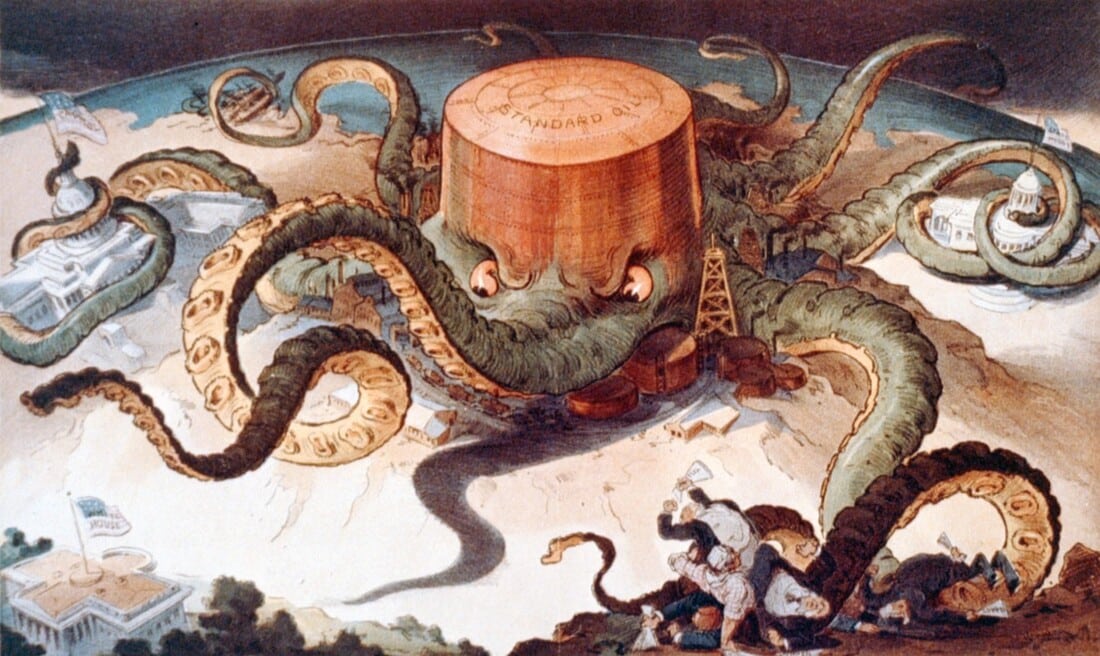

At the age of thirty, he invested everything in the development of a refinery. Taking chemist Samuel Andrews on as a new partner, he developed a new, safer and more stable process for lighting. But given kerosene’s dismal reputation, he decided to rename it petroleum. The Standard Oil Company was born.

Its prices, negotiated on the cheap in the greatest secrecy, had the effect of sinking its competitors. In the episode known as “The Battle of Pittsburg”, he managed to buy out 22 of his 26 competitors in less than two months. At the age of 33, he won the oil monopoly.

When Rockefeller finally realized that Vanderbilt wanted to do without his services and take his business away from him, he developed the very first pipeline, enabling oil to be transported over long distances in horizontal pipes. In this way, he was able to free himself from his dependence on trains. From then on, Rockefeller was determined to control the entire oil value chain, from extraction to distribution.

Carnegie, now Thomas A. Scott’s trusted lieutenant, pays the price for Rockefeller’s lack of scruples. Rockefeller, allied with Vanderbilt, decides to shut down his Pittsburgh refinery, precipitating the downfall of The Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas A. Scott’s company.

Determined to avenge the death of his bankrupt mentor, Carnegie discovered the virtues of steel, a rare material that was difficult to produce but unrivalled in its strength. Thanks to the work of Henri Bessemer, the manufacture of this metal obtained by melting iron and carbon was reduced from two weeks to 15 days.

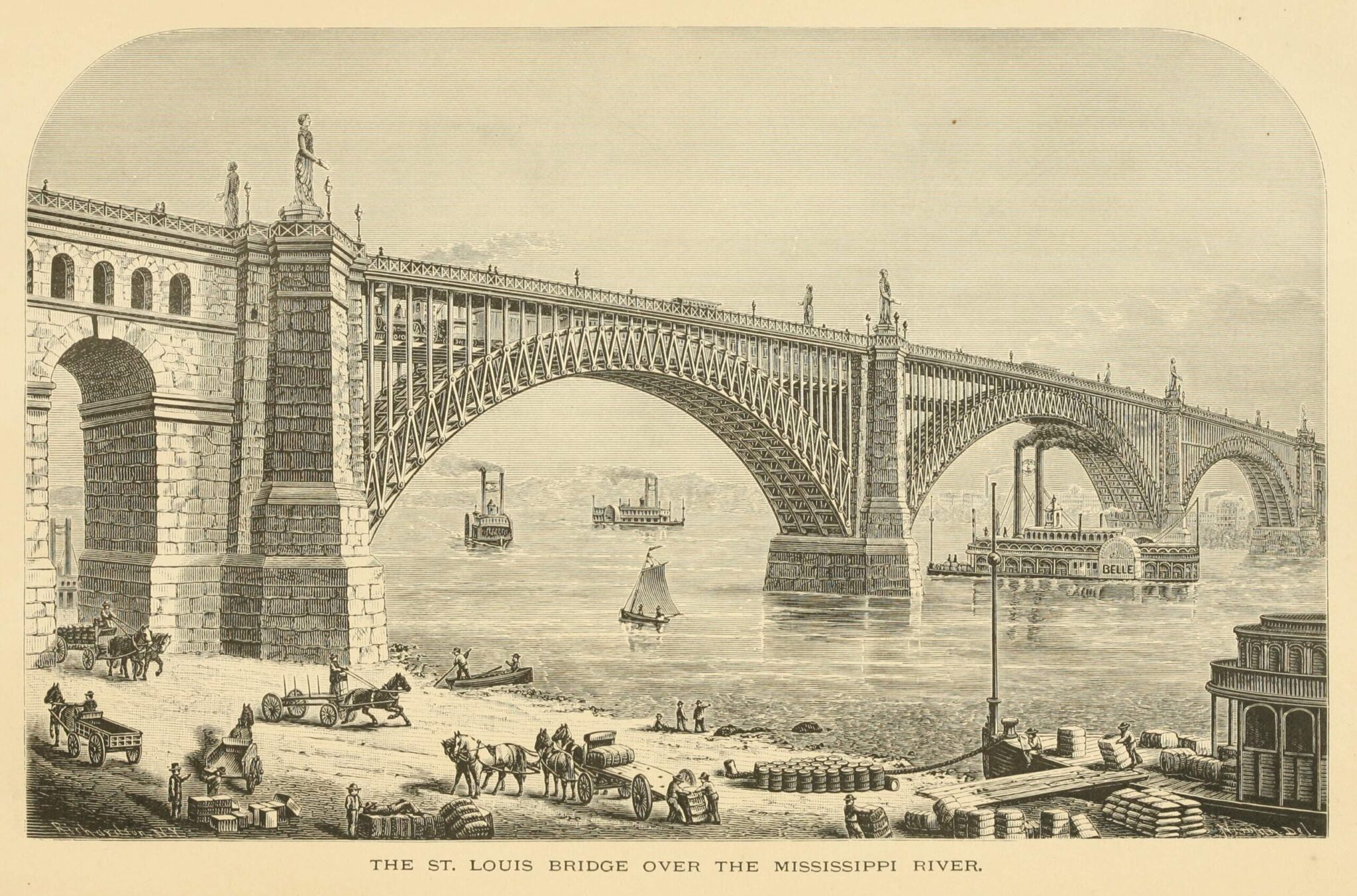

In 1873, Carnegie set out to span the indomitable Mississippi River with the first suspension bridge, the Eads Bridge. At the age of 33, he demonstrated the strength of this unknown material by driving an elephant over it, relying on a popular belief that such a pachyderm could not walk over an unstable bridge.

As requests poured in, he realized that the potential was far greater, especially for replacing wooden steel sleepers and making train journeys safer.

Unable to keep up with demand, he put all his savings into building the country’s first steel mill. This was the birth of Carnegie Steel and its gigantic 100-acre site on the outskirts of Pittsburg.

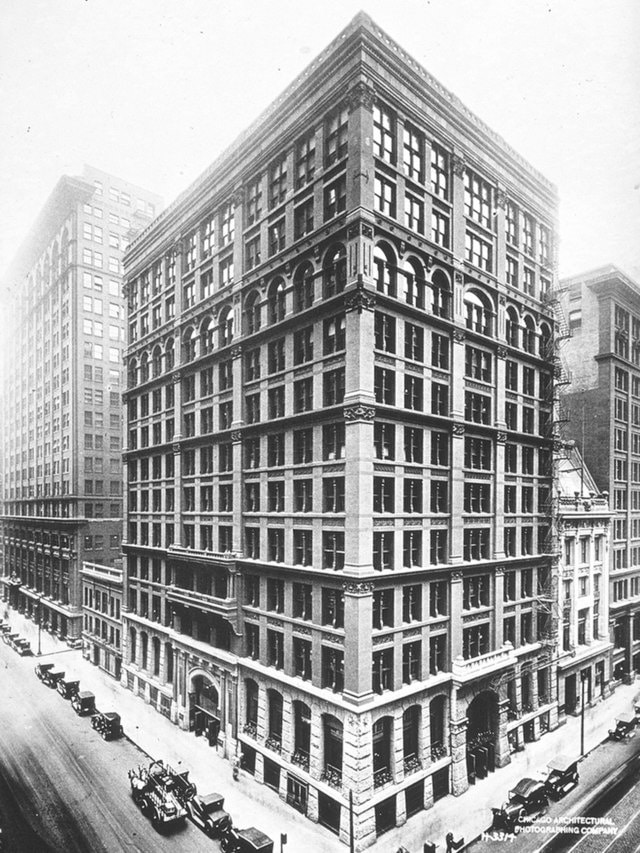

A visionary, Carnegie understood that the collapse of the railroads was inevitable, that the future would be made of steel and, above all, vertical.

On September 18, 1873, Jay Cook’s merchant bank declared itself unable to support the Northern Pacific Railway. The country was hit hard by the Great Deflation sweeping the world. Stock prices collapse, bankruptcies multiply (Jay Cooke & Company, Union Pacific…). Wall Street was forced to close for ten days, a record in its history! Millions of jobless Americans flocked to the big cities of New York and Philadelphia. So many hands were needed to build steel superstructures.

The very first skyscraper was built in Chicago in 1885: the Home Insurance Building. The 42-metre steel structure was designed by Carnegie.

The following year, Carnegie’s steel mill made it possible to build a hundred buildings in Chicago alone. Carnegie also won a monopoly on steel.

This era of lawless dominance gave rise to the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in the United States in 1890.

Working for the Greater good

If the great fortunes of the time often acted against civil society, the latter never ceased to redeem their consciences.

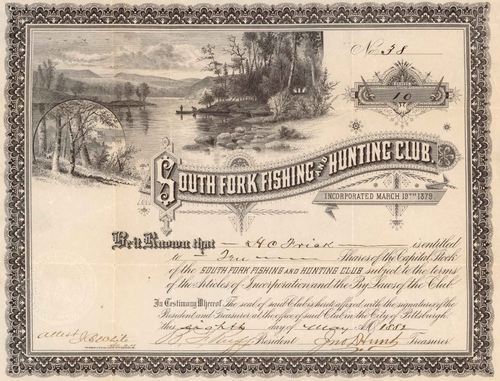

From Rockefeller pressuring his business partners on prices or breaking trade agreements for no reason, to Carnegie having his workers shot on strike because of the infernal pace he himself imposed in order to be as profitable as possible. But that’s nothing compared to Carnegie’s gangster-like lieutenant. His ultimate whim, his artificial lake for his private club, cost the lives of thousands of working-class families living below in the town of Johnstown, when the dam burst.

These days, brands are increasingly taking sides on political issues and seeking to play their part in major societal causes, a trend inspired by the mythical tycoons of industry.

Particularly pious and sufficiently wealthy, many of them carried out charitable actions or built foundations in order to “give back to society what it had given them”.

As if to ensure divine forgiveness, Carnegie and Rockefeller were among the first modern philanthropic millionaires.

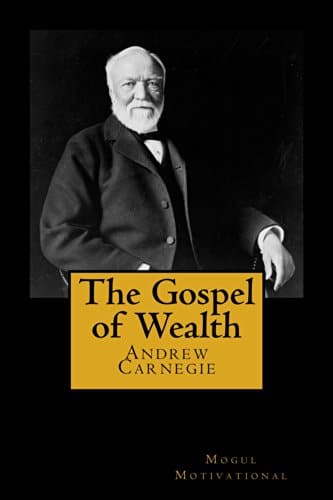

Carnegie drew a lesson from his life, which he published as The Gospel of Wealth. The book was a great success, foreshadowing the “inspirational stories” of contemporary entrepreneurs. By the time of his death in 1919, Andrew Carnegie had managed more than $350 million in the form of donations and foundations.

Rockefeller, wanting to have the last word, took great pleasure in giving more than his rival Carnegie. During his lifetime, he is said to have donated nearly $500 million to various charities, having made it a habit through his mother to systematically donate 10% of his income to the Church. By the end of his life, he had become the most hated man in America, and used to say that he was accountable to no one but God, always keeping a Bible close at hand.

He became the richest man of all time, with a fortune estimated at $200 million in 1902 and $900 million in 1914, or 1% of the US GNP at the time. This fortune would in fact be the equivalent of today’s $200 billion. In addition to oil, Rockefeller diversified into automobiles and aviation. His fortune was used to finance the construction of the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Institute, modelled on the Pasteur Institute.

Cornelius Vanderbilt was responsible for the million-dollar endowment that enabled the construction of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. For him – like Rockefeller – fortune is earned. A precept sufficient to disinherit all but the most capable of his children. When Vanderbilt died, his other sons and daughters fought over their father’s will for $100 million in assets and savings.

Old Money style is back with a vengeance this year on social networks and TikTok in particular. Many of the properties left over from this era are as big as Xanadu, the home of Citizen Kane’s hero. To find out more, watch The Men Who Built America on Amazon Prime Video and/or the excellent Arte documentary Capitalism History – The Gospel of wealth.

Read also > TAYLOR SWIFT: A MONEY-MAKING PHENOMENON

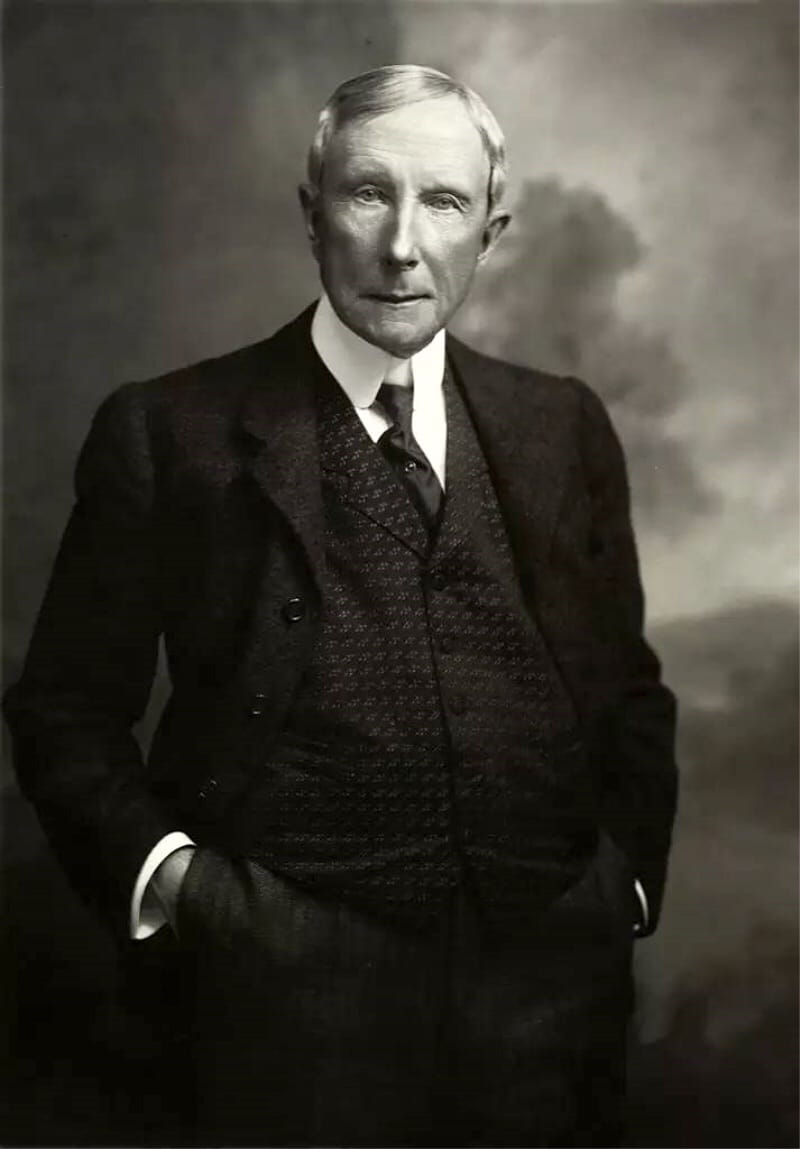

Featured Photo: The Men Who Built America © Prime Video